2. Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Research Questions - July 2024

- Introduction

- Context of game making and digital projects at home and other informal settings

- A review of relevant research informing computer game design and programming (CGD&P)

- Deconstructing the concept of constructionist gaming AND for the aim of (HOW DOES THIS HELP THE PROBLEM STATEMENT?)

- Pedagogies to support game making via coding

- Programmes working to address challenge

- Synthesis of chapter / discussion / problem statement

- Holding Zone / For the Chop?

- Barriers to participation in game making practices (explored in contextual settings)

- Game making and coding and in schools and formal education

- Context of game making and wider digital making and culture home and informal settings

- Game making and maker culture in non-formal learning contexts

and third

spaces

- Physical spaces which suit non-formal approaches

- Sketchy pedagogies

- Funds of knowledge and third space

- Third spaces and the context of this study

- Game making as a fund of knowledge

- Work in non-formal settings drawing on home interests

- Mozilla - Teach the Web as context and community

- Mantle of the Expert - processes drama used in teaching technology

- Situating Computational thinking within curricular concerns

- Studies exploring CT as an pedagogical framework to support learning computer coding

- To perhaps add to Lit REVIEW

- Project Based Learning (PBL)

- Project Based Learning as an inclusive pedagogy

- Complications with Project Based Learning

- Game making and Project / Problem Based Learning

- PBL and Authenticity in the domain of teaching programming

- Issues of Inclusion and PBL addressed through UDL principles

- MDA and conceptual game elements framework

- Synthesis of chapter / discussion - PREVIOUS

VERSION

- Problematising distinctions between instruction-based tutorials and unguided approaches - towards guided participation - FOR DISCUSSION

- Deficit of cultural processes & appropriate frameworks to support community-based coding for beginners

- Tensions surrounding authenticity of tool use

- Sythetis of current Responses to challenges presented - MOVE LATER?

- Synthesis and analysis of models of responses to address the problem

- Removed

- Curricular concepts, semantic waves and PRIMM

Literature Review

Research Questions - July 2024

- What contradictions arose in participation in this research’s game coding processes and what pedagogical tools and processes are available to address these contradictions?

- How can game design patterns support the development of computational fluency in novices?

- How can learners build agency in an evolving community of game makers?

Introduction

This chapter reviews the literature to summarise research addressing the aims of this study. It explores several broad themes to establish a comprehensive understanding of the field. Firstly, I examine the findings of research and reviews in the areas of computer game design and programming. Following this, I outline key barriers to participation to game making identifying factors of technical, cultural, and practical dimensions. The review then delves into key pedagogies of game making and digital making. A significant focus is placed on the use of game design patterns (GDPs), where I highlight their use in computing education. This includes analysis of a strand of research investigating the use of collections of GDPs by novice game designers. Additionally this chapter examines the learning characteristics of informal settings for game making such as, code clubs, competitions and game jams. Subsequently, I explore how this review has informed the proposed problem statement of this thesis, emphasising the need for developing novel and robust pedagogies in this area which support learner agency. This sets the stage for subsequent exploration of agency in Chapter 3, which outlines the the theoretical framework of the study. By addressing these themes, the literature review not only situates the current study within the broader academic discourse but also underscores the importance of innovative pedagogical approaches in fostering inclusive game making communities.

Context of game making and digital projects at home and other informal settings

The processes and motivations driving of home education are varied [@fensham-smith_invisible_2021]. These motivations are often categorized into two broad streams: pedagogy and ideology [@galen_home_1991; @rothermel_can_2003]. Addressing ideology, some families choose home education to limit their children’s exposure to mainstream values, such as religious beliefs or consumerist ideals. In terms of pedagogy, popular concepts within home education circles include unschooling and deschooling. Holt’s concept of unschooling [@gray_challenges_2013] emphasises facilitating learning by drawing out children’s interests through everyday activities. Illich’s work on deschooling promotes the idea of webs of learning [@illich_deschooling_1971], where learners access educational experiences in varied contexts based on their interests and needs, rather than relying on a single educational institution as the sole source of knowledge. Many home-educating families actively seek and establish networks, using friendships, social networking groups, and email lists to share opportunities and collaborate on learning activities [@doroudi_relevance_2023]. The game-making club that forms the basis of this research can be viewed as one node within the complex web of learning that participating families engage with.

The term informal is examined briefly here using two dimensions: setting and educational structure. While definitions of informal education are complex, the term generally refers to learning that occurs outside a traditional school environment [@erstad_identity_2012]. However, as Sefton-Green [@sefton-green_literature_2006] notes, formally structured learning can take place in informal settings, and vice-versa. Others writers [@eshach_bridging_2007, p. 173; @werquin_recognition_2009] use the term “non-formal” describe learning that happens outside of formal institutions, which may involve little instruction but still comprises a carefully planned learner experience, contrasting with both formal and unstructured (informal) learning. This study uses the term “non-formal” in this way, while “informal” is used more loosely to indicate learning activities happening outside a classroom lesson.

Turning to the structural dimension of education, there is also a lack of a clear division between formal and informal approaches [@rogoff_organization_2016]. Rogoff outline a false dichotomy between children-led (based on free exploration), and adult-led (focused on direct instruction) approaches [@rogoff_observing_1995, p.211], proposing instead a more complex community-based understanding of learning that includes concepts of guided participation and apprenticeship [@rogoff_developing_1994]. These concepts are explored in more detail in the following chapter. For now, it is sufficient for the discussion of this chapter, to introduce guided participation as a process of active involvement in cultural and social activities, under the guidance of more experienced individuals under the guidance of more experienced members, offering an alternative to the simplistic children-led/adult-led spectrum.

A review of relevant research informing computer game design and programming (CGD&P)

Before addressing studies directly focused on computer game design and programming (CGD&P), it is relevant to examine an area that in part stimulated the interest and motivation to explore the area of game making as a potential vehicle for diverse learning outcomes: specifically digital media and game making, and meta-gaming in informal communities. Observations of young people’s enthusiastic involvement in online communities discussing gaming culture and related creative activities sparked questions on how to leverage this interest for other educational aims [@gee_what_2004; @papert_mindstorms_1980]. Gee [@gee_what_2004] frames these informal, often online communities as affinity spaces where activities and culture created around games are termed meta-gaming. He examines how shared discourses and emerging identities develop within these spaces. Researcher Mizuko Ito’s ethnographic approach to studies of informal digital consumption and making in the home [@ito2013connected; @ito_hanging_2010; @ito_living_2009], charts a progression in proficiency of young makers of digital products within online communities. This approach, connecting the affordances of new online tools with the sociocultural view of learning as embedded within social and cultural contexts, is well represented via case studies and is framed a pedagogical approach described as Connected Learning in a book of the same name [@ito2013connected]. One of the contributors, Sefton Green [@sefton-green_mapping_2013] explores the wider context of digital making including anxieties around the use of digital technology by young people and and it’s alignment with valued digital skills required by the workforce. He notes both the potential and current lack of research on the transfer of learning opportunities and learner trajectories between informal experiences, formal learning settings and professional destinations.

Turning more specifically to studies on computer game design and programming (CGD&P), several notable reviews explore the motivations, processes, and impacts of making games for learning [@denner_does_2019; @earp_game_2015; @hayes_making_2008; @kafai_constructionist_2015-1; @gee_video_2016]. While Gee and Tran [-@gee_video_2016] discuss the diverse tools available for game design, Hayes and Games [-@hayes_making_2008] take a broader approach, identifying four main motivations for CGD&P: learning computer programming skills, deepening subject knowledge of other curricular subjects, involving more girls in computer programming, and using game design to understand design concepts. Kafai and Burke’s review [-@kafai_constructionist_2015-1] , which synthesises 55 relevant papers within the framework of constructionist gaming, largely maintains these categories but adds new dimensions. These include studies addressing race-related barriers to participation and social dimensions such as pair programming, social skills, self-reflection, cultural awareness, and a range of technical abilities that facilitate participation in the information society. Collectively, these competencies are framed as 21st Century Skills [@bermingham_approaches_2013]. A review by Denner and colleagues [@denner_does_2019] focuses on computer science learning, breaking this broader concept into subcategories of programming knowledge and problem specification and design.

The narrative and celebratory nature of Kafai and Burke’s review contrasts with the systematic approach of Denner et al. [@denner_does_2019], who make more modest claims. However, Denner et al.’s finding are also positive about the the effectiveness of CGD&P to develop computing science learning and motivation. While Kafai and Burke’s review highlights the broad potential of CGD&P and the barriers to participation (explored in the next section of this chapter), their discussion of pedagogies is limited and expressed in general terms [@illingworth_review_2017]. Denner et al. [@denner_does_2019] outline three strands of pedagogical interest: design-build-test, stepwise instruction, and social pedagogical approaches. However, these strands are described only in vague terms, which is frustrating given their stated intent to provide a systematic review and the lack of similar breakdowns in other reviews. Later in this chapter, I explore these strands and analyse the pedagogies used in this field in more detail.

Barriers to participation in game making

This section explores relevant studies to outline the barriers to participation in CGD&P, addressing three key areas: technical barriers, access to suitable technology and environments, and issues related to identity and values.

CGD&P inherits some of the intrinsic difficulties associated with computer programming [@sentance_teaching_2019; @gomes2007learning; @joao_cross-analysis_2019]. These difficulties include the complexity of programming syntax, the challenge of understanding abstract concepts, and problems with transferring skills between different contexts [@gomes2007learning; @rahmat_major_2012]. To address these issues, specialist coding tools, such as block-based coding environments, have been developed for novice coders, particularly younger audiences. These tools aim to simplify coding syntax, project organisation, and the overall complexity of the coding environment [@yu_survey_2018]. However, this simplification creates a tension between using more authentic programming languages and relying on scaffolded, specialised approaches [@joao_cross-analysis_2019]. Sefton-Green [-@sefton-green_mapping_2013] explores this tension in the context of digital making, contrasting Mozilla Webmaker tools (which use web languages like HTML, CSS, and JavaScript) with block-based systems like Scratch, which can obscure learners from authentic code languages.

Regarding access to CGD&P, one significant barrier is the inequality of access to participatory culture communities. Historically, the lack of access to the necessary technology, such as high-cost computers, was a major issue [@resnick_computer_1996]. While equipping community centres with computers may have addressed some of these concerns, technological access is only one dimension of the problem. Sefton-Green [-@sefton-green_mapping_2013] argues that motivated and capable facilitators are crucial for enabling participation, suggesting that even with improved access to equipment, many young people still face barriers. The full potential of online metagaming communities, as described by Ito and Gee [-@ito_hanging_2010; -@gee_what_2004], remains largely inaccessible to the majority. Among those who do participate, creative activities that result in finished digital products are rare, with studies such as Luther et al. [-@luther_why_2010] revealing an 80 percent failure rate in collaborative media projects within the New Grounds community.

Addressing barriers linked to identity and values, a key theme in CGD&P is the potential for games to increase inclusivity for those traditionally excluded from computing cultures [@kafai_beyond_2014]. There is significant potential to leverage home interests in computer games to bridge into more structured computing activities. The widespread appeal of casual and retro gaming, alongside the proliferation of retro games in popular culture, offers a rich repository of knowledge that can be utilised in various educational contexts [@moje_working_2004]. However, Kafai and Burke balance this potential with complex issues of the gender representation associated with gaming culture [@kafai_diversifying_2017].

Addressing gender-based barriers to participation, Papert and Turkle [@papert_epistemological_1990] identified some girls’ alienation from abstract computing approaches. They emphasised the need for diverse teaching and learning styles to address issues surrounding the early socialisation of women and girls, advocating for the inclusion of personal and concrete working styles. Denner and colleagues [@denner_what_2008; @angelides_beyond_2014] highlighted that inclusive gender practice in game making involve allowing participants choice over both the content of their games and the dominant mode of play (game mechanics). Their findings present a nuanced view of girls’ interests in game genres and support research cautioning against gender stereotyping and rigid identities in this area [@pelletier_gaming_2008]. Kafai and Burke [@kafai_beyond_2014] address gender identities within game design by advocating for the creation of new communities and learning environments that align with participants’ values, rather than attempting to draw girls into existing, male-dominated spaces. Similarly, Buechley et al. [@buechley_lilypad_2008, p. 431]question, “How can we integrate computer science with activities and communities that girls and women are already engaged in?”

Margolis et al. [@margolis_stuck_2008;] outlined barriers contributing to a racial gap in computing participation and achievement in the US, including feelings of isolation, limited access to computing opportunities, and a lack of social support. DiSalvo and colleagues investigated these barriers within a game testers programme, examining how an interest in computer games could motivate access to computing education [@disalvo_saving_2014; @disalvo_glitch_2009-1; @disalvo_learning_2008]. Their findings indicated that activities should not only be engaging but also align with the underlying values of the programme’s young, African American male participants. Vossoughi et al. [-@vossoughi_making_2016] critique digital making cultures, stressing the need to integrate not only the values but also the cultural experiences of working-class students and students of colour into the making process.

Exploring pedagogies of constructionist gaming

This section explores Kafai and Burke’s framing of constructionist gaming as a dominant voice in the field, situating the concerns of this thesis within the existing body of research. To achieve this, I will examine criticisms of constructionism, particularly its perceived lack of a specific pedagogical approach.

Laurillard provides a clear summary of constructionism as a distinctive and productive pedagogy but notes that ‘theoretical underpinnings of constructionism are difficult to pin down in most of its literature’ [@laurillard2020significance, p.29]. Her definition is based on Papert’s vision of a publicly shareable project within a microworld environment (a concept explored later in this chapter), designed to foreground specific concepts. However, this narrow and clear definition contrasts with the broader use of the concept by Resnick [-@resnick2014give] and other constructionist researchers, particularly in their advocacy for software and hardware tools that promote an open-ended, child-led approach to designing engaging and relatable objects of interest.

Research on constructionism as an educational approach has increasingly centred on the design affordances of researcher-created toolkits and communities that facilitate personal understandings of knowledge [@vossoughi_making_2016]. When pedagogy is addressed in recent constructionist studies, it generally takes the form of broad principles of design and project-based approaches [@resnick_scratched_2012; @resnick_lifelong_2017], which will be explored further in this chapter. Recently, Kafai has revisited the topic to emphasise the importance of a situated and critical approach to coding practices [@kafai_revaluation_2022; @kafai_theory_2020]. However, this work remains broad, and specifics on pedagogical scaffolding are still lacking. Vossoughi’s [-@vossoughi_making_2016] critique of constructionism from a socio-cultural and egalitarian perspective highlights this absence of intentional forms of pedagogy. She attributes this gap to a focus on tools rather than on sociocultural contexts and the development of social relationships as part of the making process.

Vossoughi and other researchers also highlight political and social concerns associated with constructionism [@thumlert2018learning; @vossoughi_making_2016]. They argue that a constructionist approach can implicitly favour coding as a pathway to joining the computer programming industry and developing employability skills in young people. Thumlert and colleagues caution against the appropriation of skills such as creativity and ‘design thinking’, which they argue are increasingly co-opted by market-driven agendas rather than being used for critical and emancipatory purposes [@thumlert2018learning, p.4]. They also warn that this positioning could lead to the integration of constructionist approaches into instruction-based models that are narrowly focused on curricular concerns, rather than fostering the development of computational fluency, which supports learners’ expression within a community [@thumlert2018learning].

Given the importance of more intentional pedagogical approaches in this area and the lack of detail in the reviews described above, the following sections will detail several key pedagogies used in CGD&P.

Pedagogies to support game making via coding

One of the main themes of this review is to explore the pedagogies available to support coding, particularly in relation to Research Question 1 (RQ1). In the context of activity theory, pedagogy can be framed as pedagogical tools and processes, functioning as a type of mediational strategy. The following discussion focuses on pedagogies that are especially relevant to digital making, specifically game making, in informal, real-life (as opposed to online) communities. Denner’s [-@denner_does_2019] systematic review of game making studies, identifies three main pedagogical streams: design frameworks (Design-Build-Test), step-based pedagogies, and social approaches. This section will broadly follow these streams. First, I will review design thinking approaches and project-based learning. Next, I will outline pedagogies centred around scaffolding game production through progressive steps, such as the Use, Modify, and Create (UMC) framework. Finally, I will examine the social and cultural aspects of coding clubs and informal programmes that serve as venues for CGD&P.

Design frameworks using stages

Many design frameworks exist in diverse areas of production with varied degrees of adoption. One stream in CS stems from engineering and design thinking [@resnick_all_2007; @winarno_steps_2020-1].

Resnick [-@resnick_scratched_2012] describes the foundations of the design-based approaches in education as; engaging in design activities, exploring personally meaningful topics, collaborating with others, and deepening understanding through reflection. The key reason to adopt these principles is to increase engagement via sustained participation in computing projects for a broad range of learners. To illustrate this design-based approach Resnick advocates a creative cycle model [@resnick_lifelong_2017]. The five circular stages are; Imagine, Create, Play, Share, Reflect and returning to Imagine once more. This model is a more adapted from many similar expressions of iterative design stages in the domain design thinking to focus on more individual ideas of creativity. See figure 2.x for one example from the Stanford dschool [@dam_5_2024].

{width=90%}

{width=90%}

Figure 2.x. Design thinking via design stages model from Stanford dschool

One of the sources for sustained engagement is when, as part of the iterative process, learners are able to test and then revise their creation or experiment based on their own evaluation. Another factor is the importance of a community in the design process, as a real audience for creations, as a source of inspiration and as peer evaluators in the testing process.

While the value of design thinking stages for educators planning sessions seems clear, and elements of this framework are included in early literature to help adoption of new computing curriculum in UK [@csizmadia_computational_2015], there is little research exploring how the stages could be used by learners to scaffold their own design process when engaging in making digital products. Resnick and Brennan [@mouza_imagining_2013] focus on the affordances of tools and communities to support all aspects of students work on design stages without suggesting any processes from a teacher of student perspective. One exception is the work of Zainal et al [@zainal_review_2021], using the Stanford dschool design thinking framework [@dam_5_2024] to structure the work on students in undertaking IoT project work. The authors, note the lack of research investigating the potential of this approach and call for more work to be done in this area. ADD TO THE PROBLEMS STATEMENT.

The model is similar to the ADDIE model from instructional system design: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation and Evaluation. The discipline of teaching engineering also has a similar design stage cycle with many contesting variations [@winarno_steps_2020]. Engineering is Elementary project adapted from the ABET (Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology) guidelines [@syukri_impact_2018] involves the following steps; Ask, Imagine, Plan, Create, Test, Improve, Share [@hester_engineering_2007]. It has been adopted by the area of computing is one used in a recent book on coding by Bers [@bers_coding_2021]. HOW IS THIS USED? AS A PEDAGOGY?

Thus, while the ethos and benefits of this approach are convincing RESNICK’S TAKE, what is not clear however is who this framework is for (either for designers, facilitators or participants) or how it can be activated in the process of facilitating project work.

Project-based learning (PBL)

PBL provides a wide scope of research detailing pedagogical approaches aligned with the aims of this research.

The educational strategy of learning how to code games in a informal setting lends itself to a project based learning (PBL) approach. The following section explores relevant elements of PBL pedagogies, where possible making alignments with existing game making studies. In broad terms, PBL is an educational strategy which advocates: learner choice in projects which increases motivation; authentic and shareable project outcomes and learning environments to encourage peer feedback and reflection; iterative projects work supporting student mastery; and challenging goals and guidance in goal setting aiding self-regulation in learners [@barron_doing_1998; @hernandez_aalborg_2015].

PBL requires learning environment and activities that allow for an active construction of knowledge by learners rather than one dominated by instruction [@kokotsaki_project-based_2016]. PBL pedagogy aligns with AT concepts of learning in that change happens via the use of artefacts use in a community [@gibbes_project-based_2014; @hung_activity_2000].

<!-- Encourage Student Choice: Darling-Hammond et al. (2008), Larmer and Mergen- doller (2015a), Ravitz (2010), and Thomas (2000) all noted the importance of student choice, autonomy, and authority. [@kokotsaki_project-based_2016, p. 9] -->

Critics of PBL often wrongly conflate it with unstructured, pure-discovery approaches [@kirschner_why_2006; @hmelo-silver_scaffolding_2007]. In formal education, contextual factors hinder the adoption of PBL challenge creative approaches in general. These include challenges of teaching to an exam-based curriculum, time allocated and other timetabling factors. While these are less applicable to informal settings, other challenges still exist including, lack of frameworks, expertise, confidence in facilitation [@ertmer_essentials_2015-1]. In addition, the range of applications and situated nature of the learning via PBL creates significant challenges in representation of practice, including communicating specific details of scaffolding used.

Studies and supporting resources advocating PBL articulate various procedural forms of scaffolding which facilitators can adopt, including those to aid group work, support reflection, and to structure knowledge sharing via project outcomes [@ertmer_essentials_2015-1; @pitot_establishing_2024]. An additional form of of PBL scaffolding, the restriction of choice of participants to reduce the possibilities for learners being overwhelmed, can expose a tension in relation to the value of student choice over project work [@ertmer_essentials_2015-1].

PBL can be effective in diverse fields of practice including: inclusive pedagogies [@leggett_impact_2021], and the use of appropriate “learning scaffolds” [@kokotsaki_project-based_2016, p. 8], language learning [@gibbes_project-based_2014], and digital making [@weng_characterizing_2022]. However, due to the difficulty of generalising and abstracting frameworks linked to domain specific knowledge and processes, a gap exists in PBL literature regarding kind of scaffolding that might support the develop CGD&P more specifically.

Pair programming & social/collaborative coding

In their review of the potential of CGD&P to encourage collaboration, Earp and colleagues found that “analysis of collaboration is mainly restricted to peer review and providing feedback” [@earp_learner_2013].

Pair programming, a common industry practice has recieved attention in educational contexts [@hanks_pair_2011]. Pair Programming groups students in pairs and divide coding two into two roles. One student undertakes hands-on coding while the other is free to think about more the abstract design of the overall program. A benefit of pair programming is to increase coding confidence as students build their experience of the different roles involved in coding. To help novice coders teachers should model and break down the processes involved.

Werner and colleagues [@werner_pair_2009; denner_computer_2007] investigate pair programming as way to adress gender gap and extending research on collaborative problem solving in computer coding.

They cite research challenging the gender aspect of bricolage / abstract duality, but propose a need for more research on programming styles and strategies [@denner_computer_2007] Their own research underlies that while pair programming is an inclusive strategy beneficial to all but in particular to narrow participation gaps due to gender and socio-economic factors [@werner_pair_2009, p.31].

In Denner’s research, pair programming involved social learning elements and can model a greater choices for students in they way they solve problems and opportunities to develop identities. The process of building an identity in a community with the help of peers is key to a socio-cultural understanding of how learners pick up coding in a classroom (or other settings).

Werner et al draw on existing research on collaborative ‘social reality or joint problem solving space’ to scaffold the process of ideation [@omalley_construction_1995] and the role of friendly relations to develops these productive and sustained interactions [@mcdowell_pair_2006].

Bring in limits and extension of research on pair programming to wider groups / more flexible processes [@preston_using_2006] -

- resource interdependence from Preston

Links to other pedagogies in this work. UMC and Use of game design patterns [@werner_computational_2020]

Use Modify Create

The ‘Use-Modify-Create’ approach proposed by Lee and colleagues [-@lee_computational_2011] is particularly promising to counter issue of user anxiety and demotivation surrounding the difficulty of coding games. UMC evolved from research involving the use of game making and robotics to support computational thinking [@denner_computer_2012; @denner_using_2014; @werner_pair_2013; @werner_children_2014]. The model advocates the remixing of existing games to act as a scaffold to build the competence of the beginner coder. Learners are guided to progress in the complexity of their modifications, thus becoming increasing proficient in the recognition and use of computational concepts and structures [-@lee_computational_2011]

In the Use stage, coders build a familiarity with coding interfaces, code structures and syntax through scaffolded approaches which involve interacting with the program code and what it produces. In the Modify stage learners progress to working on real projects created by others. Learners deepen their knowledge of coding structures and practices by altering existing projects and templates to suit their own aims. Create: After novice coders become more familiar with patterns of code design in use in the modify stage, they can progress to replicate such patterns in other code that they create from scratch.

A study involving five hundred 9 to 14 year-olds found that the UMC approach can balance a structured approach with more student-led exploration [@franklin_analysis_2020]. The researchers also found that the students enjoyed the UMC approach as they had more choice and agency in the process. This is supported by other research which compared UMC with a starting-from-scratch approach and found higher student engagement for those in the UMC group [@lytle_use_2019]. The researchers found that because students using UMC had more time to play around with code, they were able to add their own personal touches and that this ownership over the code sustained their continued engagement. While the scope of the study is limited, observations support motivation of UMC that this pattern of creation maintains higher level of engagement through reducing technical barriers to participation, and affording greater sense of learner’s ownership over end project through greater choice over the final outcome.

Research on UMC which develops learner choice

UMC has been developed to be end with scaffolded set of choices. In a study where students use a block based language to develop simulations - the authors note limits of study but are enthusiastic about providing a limited set of choices for final exploration within a limited time frame [@lytle_use_2019-1; @lytle_use_2019]

- Scaffold Students and Teachers- Providing the necessary programming blocks students need to complete a choice

- Differentiate Choices by Difficulty - create choice systems that have varying difficulty

- Create Choices that Show Visible and Immediate Changes

- Make things Complex, not Complicated

- Draw from Student Desires - students will engage more with the material, feeling like the creations are their own.

LINK The main concept of UMC is remixing a game to build. Scratch has been instrumental in bringing this methodology into clubs and classrooms as an explicit feature of its online community. FIND SOURCE

Curricular concepts, semantic waves, LOA

A common pedagogical strategy is to align learning activities with knowledge and competencies outlined by a curriculum. A common line of game making research follows this logic to align game making with curricular contents, in particular computational thinking concepts.

Tedre and Denning’s [-@tedre_long_2016] review of CT cautions against a too narrow definition of CT that highlights formal abstractions as represented by Wing’s take on CT [-@wing_computational_2008]. This is not to argue that Wing’s approach to CT is without technical merit [@lodi_computational_2021], rather that its adoption by educational bodies like CAS in the UK and similar bodies internationally has risks. The inclusion of formal CT frameworks in curriculum and formal testing has provoked mechanistic teaching of decontextualised concepts via formal teaching methods to the detriment of hands-on exploration and creation of personally meaningful projects [@resnick_coding_2020].

In teaching computing pedagogy the concept of levels of abstraction can be taught to students to help them understand the level of abstraction that they are working at [@statter_teaching_2016; @waite_abstraction_2016; @waite_abstraction_2018-1]. To quickly review LOA, the levels are Problem, Design, Code, Running the Code. And the purpose is, “Levels of abstraction has been interpreted as a hierarchy to enable teachers and learners to describe which level they are working at, rather than as a methodology for programming projects.”[@waite_abstraction_2018]

Semantic Profiles and Waves

Introduction to semantic waves.

[@maton_making_2013]

SWs - PICKED UP IN UK OFSTED report [@ofsted_research_2022] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-review-series-computing/research-review-series-computing

CT instruction can be aided with a focus of teachers on semantic profiles and waves.

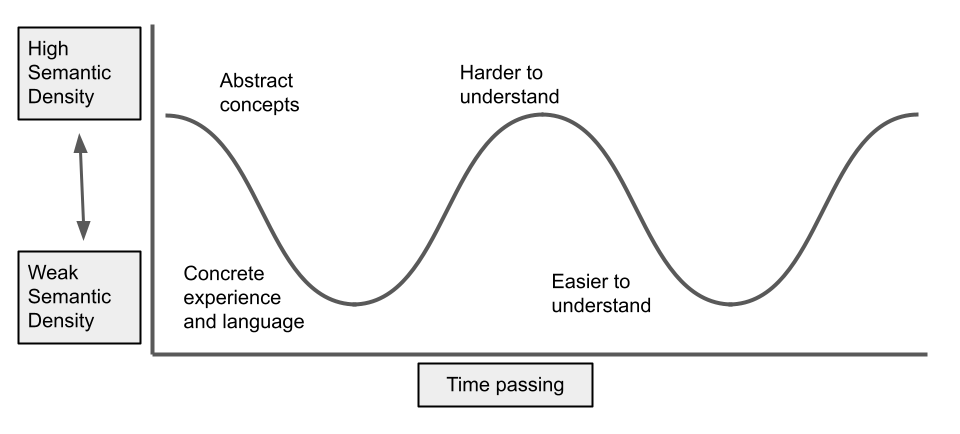

Semantic profiles chart the use of more concrete (high semantic gravity) language and more abstract (high semantic density) concepts and patterns as they emerge in classroom situations [@macnaught_jointly_2013]. Exploring semantic profiles is being promoted by NCCE an aid to teachers wanting to plan their lessons in a way that communicates the key abstract curriculum knowledge that students will need for exams, and to also allow them to put the concepts into practice to build real coding skills and to make valuable connections to personal experience. A Quick Read on semantic profiles is available on the NCCE website.[^2]

Research carried out by Curzon and colleagues [-@curzon_using_2020] in a computing education context outlines the value of semantic profiles in wave shape as opposed to a flatline which remains too much in concrete examples or more abstract concepts. This research highlights the value of unpacking, exploring and then repacking ideas during the course of a lesson. A student’s understanding of a concept may deepen a little bit each time it is applied in practice and then reconnected with the abstract.

Figure 3.1 A Semantic Profile with Semantic Waves

Examples showing semantic wave profiles usually start with the process beginning with the abstract or with high semantic density. See Figure 1.1 for an example. The advice of starting with more abstract terminology and concepts may seem to be in opposition to the approach of Concreteness Fading as explained with the CRA method outlined above. However, on examination of the research example carried out in the research above, the process of starting with concepts may only involve giving a short outline of the concept that is being explored and saying that this will be illustrated in a following concrete activity.

PRIMM

PRIMM uses concepts of semantic profile to try to align instruction based approaches with a sociocultural approach (or at least some hands-on approaches)

In proposing PRIMM Sentence et al highlights a debate in this field of a proposed deficit of exploration based, constructionism approaches by Grover [-@sentance_teaching_2019, p. 5], proposing greater instruction and guidance. To address this without fully embracing an instruction, expert-led approach, the author propose PRIMM model, signifying Predict, Run, Investigate, Modify and Make.

Thus, PRIMM extends the UMC model, Modify, adding three stages to the start. Learners are presented with a providing a concrete code example and predicting what it will do, checking the results against they running it. With guidance learners investigate possible changes that can be made to the code before modifying it. The final, Make stage (as with Create in UMC) suggests students creating programs or larger elements of code structures from scratch.

Noting recent calls align computing education with sociocultural approaches [@tenenberg_out_2014], the authors draw on concepts, of mediation and ZPD. These principles are put into action, in part, through drawing on carefully selected content from the social plane [-@sentance_teaching_2019, p. 2].

PRIMM has been developed with the the computing classroom in mind, drawing on concepts such as differentiation to make concepts accessible by all learners in a class. Prediction of a code allows a whole class of learners to unpack and repack the key computational concepts or process.

While the importance of explicit instruction of concepts is outlined, there is no guidance on what concepts should be best explored via this pedagogy. Given the context of of computing, there may be an implicit assumption that teachers turn to the UK curriculum perhaps for guidance. To illustrate this, PRIMM has been implemented, in resources aimed at UK teachers, in a way that explicitly links to curriculum concepts. https://www.barefootcomputing.org/resources/crystal-flowers-primm-1

Data from research, response of teachers .

PRIMM while suitable to schools, is not incompatable with informal environments, PRIMM process does not need to happen as whole group activity. For example teachers adapted the process, so quicker students did more than one. In addition, the authors use the metaphor of learning coding as a multi-layered and faceted process like a patch work quilt. As learners develop coding practices then built up patches, each one making the participants’ knowledge less holey. (Clear, 2012) in [@sentance_teaching_2019, p.5]. The middle ground PRIMM aims for between instruction and free experimentation may align well with non-formal approaches in non-classroom settings.

PERHAPS IN SYNTHESIS - MOVE? As a critique of PRIMM, while the authors do link to some sociocultural concepts, it is limited in the extent to which the learning environment is addressed, compared to some of the other approaches of this chapter, particularly PBL which has a shared driving question on challenge that the learning community addresses together.

Limits of the Sociocultural ideas in UK computing research (above)

MOVE? Waite et al. [@sentance_teaching_2019] cite the Block Model, [@schulte_block_2008] as potential in helping teacher structure lessons. Within this structure design patterns can be considered as??? Is this useful?

While attending to socio cultural approaches [@sentance_teaching_2019; @hwang_using_2023], there are limits in what is covered. Less in the way of identity formation and support for that process.

Signpost later discussion.

Half-baked games as Microworlds

The concept of ‘half-baked’ games and microworlds, proposed by Kynigos and colleagues outlines which are incomplete or somehow deficient in a way which motivates learners to delve into the code and improve it. Half-baked games can be designed in a way which encourages malleability of the code in directions that the learner may find interesting [@kynigos_half-baked_2007; @kynigos_children_2018]. Thus the original game designer makes complex decisions which highlight certain affordances of the game in a way which encourages the exploration of key concepts.

This concept of builds on Papert’s concept of microworlds, simplified computer simulations or models that were conceived as controlled environments in which students can explore and experiment with maths or physics concepts in a concrete way [@harel_constructionism:_1991; @papert_mindstorms:_1980; @papert_childrens_1993]. While Kynigos’ design promoted the acquisition of computational thinking, Microworlds can facilatate the exploration of diverse concepts [@rieber_microworlds_2004].

Today, microworlds are used in a variety of educational settings, from primary schools, afterschool clubs and universities. However, the use of microworlds in traditional school settings is not unproblematic [@papert_turtles_2002]. There is a danger that the potential is ‘trivialised’[@hoyles_microworldsschoolworlds_1993] into a vehicle for instruction based processes aimed narrowed to teacher chosen curricular concepts.

Kynigos and Yiannoutsou identify a progression in the type of CT skills being used as the processing of modifying the game progresses as part of the Use-Modify-Create model moving from elements like pattern recognition associated with reading of code to ones like a creating abstracted structures and sequencing their own algorithms. Kynigos also highlights the possibilities of half-baked artefacts to build learner dialogue around the problems at hand as as ‘a communicational tool to shape a common language within the community’ 2007, p. 336).

Similarly the concept of task specific programming language [@kong_providing_2022], in research on Microworlds, has a similar motivation.

"The task-specific programming language (TSPL) is purposefully limited in the abstractions and concepts needed for the tasks or explorations in the microworld so that programming becomes much easier to learn than a complete programming language.[@kong_providing_2022]"

Design patterns

Design patterns are most commonly used for computing students at higher education to teach object oriented computing but they are also useful for all levels of learners. Design patterns are rooted in real-life incidences of problems that are often solved in a particular way. They are concrete examples of coding principles in context. Design patterns can help the development of coding communities if more experiences coders take the time to document the patterns they use in an accessible way for novice coders. For educators the use of design patterns can help support learners develop coding proficiency by providing scaffolding and modelling good design decisions. However, one of the challenges for teachers of using worked examples and design patterns is how to integrate them into student-led design challenges.

The concept of computational design patterns is well explored in the professional literature of computer programming and design [@gamma_design_1995], and has also been adopted by game designers [@bjork_patterns_2005]. Design patterns are well thought out solutions to common issues faced by computer programmers and system designers.

Research in this area points to challenges of teaching the abstract nature of traditionally shared design patterns related to object oriented coding languages but points to visual methods and games as promising tactics [@azimullah_evaluating_2020; @da_cruz_silva_fostering_2019]

Game(play) design patterns

The term game design patterns (GDP) is used in different ways. Kreimeier [@kreimeier_case_nodate] distinguishes content patterns from software engineering patterns. Software engineering patterns are used to structure code and keep it architecturally neat thus facilitating code sharing and extension. These patterns would be invisible to the end player of the game. Content patterns describe common patterns of game play and design that are visible to the player.

Eriksson and colleagues [-@eriksson_using_2019] use the second interpretation rephrasing slightly as gameplay design patterns, thus placing emphasis on the exposure to the user via playing the game. They described the utility of games design patterns as a lingua franca for game developers. Other benefits cited are GDP as a source of creative inspiration and as an aid to problem-solving.

Their research, which involved young people, builds on related research with adults with the explicit goal of learning game design. One product of this research is a list of GDP patterns as a public collection (available at http://virt10.itu.chalmers.se/) [@bjork_patterns_2005].

In a design education intervention working with 11-12 year olds Eriksson and colleagues [@eriksson_using_2019] used a collection of curated patterns to prompt learners to analyse and then propose changes to an existing collaborative game The principle goals to is to address the perceived “challenge how to make results from research work related to this within Child-Computer Interaction (CCI) field easily transferable to future CCI research.” [@baykal_using_2019] The study involved learner analysis of games, the ability to change level design via graphical (not code based) editor and co-design of proposed conceptual changes to existing games.

The process of curating patterns involve selected only 14 from a list of over 100? [CHECK]. Their selection criteria for patterns to include in co-design stages included the following concerns; concrete patterns were favoured over more abstract ones to aid the learner comprehension, patterns chosen matched the learners’ capabilities, patterns that were game mechanics were also prioritised as were pattern suggested by the learners.

Using Game Design pattern collections and code examples to help novice students.

The use of a collection of design patterns, while primarily used in professional settings, can help barriers faced by novice coders.

Werner and Denner built an ambitious assessment elements into a two year programme using Alice to make games. They built a software tool to quantify the levels of computational thinking, using a structure of thinking algorithmically [@werner_fairy_2012]. The results - a limited use of standard CT concepts by students - led them to also investigate the use of students of game mechanics as well as more traditional CS constructions [@werner_children_2012]. They began to identify use of design patterns and then combination of those patterns into large game mechanics.

To help revolve the play paradox - of learner choice vs subject exploration [@hoyles_pedagogy_1992] Franklin and friends suggest the use of the UMC framework [@franklin_analysis_2020]. Other work from UMC proponent Lytle suggests a list of extensions to choose from swapping create for choose [@lytle_use_2019-1]. Based partly on the cause of teacher stress caused by the open ended nature of the “Create” part of the model.

Other researchers used to scaffold creation of coding projects by novices [@wang_novices_2021] and note barriers students encoutered including, mapping barriers, other

GSM as example

GSM created a supporting pack for teachers which used challenges themed around categorisation of game design patterns.

The normal practice is geared towards prompts within the software with specific missions.

There is little research published on how the cards were used in practice. Limitations include

Thus while existing research show the promise of GDPs in exploring systems thinking and developing an overall sense of game design, there is a gap in the research landscape in how GDP pattern collections could be used to support novices and young people to program computer games. ADD TO PROBLEM STATEMENT

Programmes working to address challenge

This section addresses programmes which address barriers to participation in informal settings.

As such, it leaves to one side extensive programmes which provide instruction based resources online and those providing CPD to teachers as detailed in the introduction [Barefoot, NCCE, CAS].

To reflect the nature of the research questions and the existing gaps in the research in this domain, the following descriptions are particularly concerned with the development of learner identity, and structures of pedagogy used.

Coding club(houses) & Grass Roots community responses

It of interest to make a link between early influnce of the constructionist school founded by Papert and this thesis. In Mindstorms Papert makes a commentary of community organising of the learning environment in a commentary about Samba schools as “settings that are real, socially cohesive, and where experts and novices are all learning” [@papert_mindstorms:_1980]. In the same book, Papert talks about LOGO environments and LOGO culture in extravagant and idealised terms, although with little detail on how to replicate them.

Additionally, Bruckman notes “tools are not enough… Tools are effectively constructionist only when they are embedded in a constructionist culture.” (Bruckman, 1998, pp. 51-52)

Bruckman and Zagal, also studying at MIT, take from this mention an opportunity to formally study the components of a Samba school [@zagal_samba_2005] and to compare it, to a Computer clubhouse, an MIT initiative designed inspired in party by Papert’s vision [@resnick_computer_1996; @peppler_computer_2009]. To do this Bruckman and Zagal draw on the socio-cultural concept of communities of practice and other social practices including the importance of showcase events share created work and flexibility of ways of participating and a diversity of skill levels and backgrounds of participants.

UK coding clubs: Code Club, Coder Dojo and Raspberry Jam

Three similar but distinct strands of volunteer based projects started around the hot zone of 2012-2014 explored in the introduction. While, it is beyond the remit to explore all three similar models in detail, that would be interesting.

They share: a grass roots approach drawing on enthusiasts.

A large take up of enthusiastic community activity in response to a model encouraging others to organise their own events. But have struggled to maintain the skilled volunteer input imagined at the start of the program (SO what?) All three projects have been subsumed into the RPI foundation raising issues of how much it is optimal for support to be concentrated in one organisation.

They were not extensively researched during the point of more grass roots

Although research shows that only a small number of code club respondents used the resources provided to support clubs, are nearly exclusively instructional in design. resources [@aivaloglou_how_2019], presumably preferring an less-structured approach, which is not centrally supported or seemingly documented locally.

Game competitions

Competitions or challenges can be used to bridge to worlds of work and expertise outside of the classroom or beyond the bounds of the informal space.

This is present in a UK context in computing domain via Coolest project.

It is also available in specialist coding websites and communities like Scratch, although not on an on going basis.

- Research on competitions in Scratch community, [@kafai_motivating_2014; @kafai2011collaboration]

- Games for change https://gamesforchange.org/studentchallenge/

And themed games for change competitions. And via

Critique of competitions [@thumlert2018learning] is that the values of the competitions are largely embraced uncritically rather than developing and transforming practices of the learning site itself. Also there is a danger of inequality of access explored above.

Educational Game Jams

Game Jams are accelerated events encouraging creative collaboration and innovation. While the event’s premise is to promote collaboration, these events are inconsistent in their support and scaffolding of collaborative approaches [@goddard_playful_2014]. Game jams often prize innovation and originality. Recent research posits that Game Jams can be profitably used in formal education contexts [@aurava_game_2021], although there is scant guidance on how to address potentially problematic issues (list these).

Educational Game Jams share share similar motivations to game competitions. Game Jams are an accelerated production methods, like code sprint or Hackathons, they characterise by a time constrained, accelerated production ethos. Game jams draw on rapid prototyping processes, and from hackathons they add constraints to accelerate creativity [@arya_international_2013; @gabler2005prototype]. participants create games individually or in teams in a time-constrained period, typically 24 or 48 hours. Team events often take place in physical venues which may be part of a wider global Jams [@arya_international_2013]. Eberhardt [-@eberhardt_no_2016, p. 3], identifies potentially incompatible strands of Game Jams, specifically citing commercialised events and professional Game Jammers contrasted to those Jams with a social purpose with a more diverse, less target driven audience . Goddard et al have analysed the key aspects of Game Games including tools, organisational processes and rewards systems [-@goddard_playful_2014], using a playful vs. gameful spectrum from Caillois [-@caillois_man_2001].

The Moveable Game Jam [@games_for_change_get_2017], a process created a collective of New York educators, can be situated on the playful side of the spectrum. To address some of the inclusivity concerns with the format adaptations have been made. MGJ can be applied in a shorter time-frame, emphasises low-cost and both digital and analogue offline game production. It uses loosely structured activities and broad goals allowing for significant learner agency. Conversely, there are element of a more structured approaches in the steering of game outputs towards particular social goals. The motivation is to communicate fundamentals concepts of game design process to participants, in particular, the following interrelated game elements; space, goal, components, mechanics and rules. [LOCATE THIS SOURCE], To achieve this there is periodic facilitator checking of the fundamental concepts previously mentioned and the use of extensive playtesting in the process.

Creative Family Learning - Roque (and 5d?) - YES 5D COLE AND GUTIERREZ

Correa (2015), explores the role of children as brokers of technology in family environments.

The work of Roque in Family Creative Learning program is of note in the way that family members are brought directly into the making process to overcome barriers to computer coding. In response to the limitations of accessibility of online participatory culture [@roque_family_2016] CHECK THIS AND SAY HOW, Roque [@roque_family_2016] FCL study addressed it with face to face session with help from family members. In asking is how can facilitators help develop participation in community activities [@roqueBecomingFacilitatorsCreative2018], Roque operationalises Barron’s work on parental roles in a making environment [-@barron_parents_2009]. The research team created a detailed guide to replicate the programme [@leggett_family_2017].

Roque makes a convincing case for the unpicking of the supportive and collaborative roles of parents and facilitators to build this capacity and awareness of family learning roles. However, while the design of the FCL programme was effective to build parental confidence and to increase overall accessibility to the process , it left questions unanswered about the effectiveness of the process to enable further learning at home after the programme end. In addition, similar to the computer clubhouse model, it is noteable that there are potential difficulties of scaling this hybrid approach (FCL) in terms of the expert facilitator help needed.

To compare with learning in more formal structured, and more naturalistic learning environments, it best matches a more optimal approach to game making with families. It is a shame that FCL is not described in more detail with sociocultural concepts.

A final reflection

In the following section, I summarise the chapters findings and clarify the problem statement of this thesis.

Synthesis of chapter / discussion / problem statement

A shorter summary leading up to the detailed problem statement of the thesis.

Including some of the following elements

- **Guided participation: **There is a stream in the research which critiques not-only instruction-based approaches but also child-led discovery within magically designed tools and communities. Rogoff’s take on guided participation as between these poles informs this study.

- Tensions surrounding authenticity of tool use: my desire to link with developer communities and the world of open sources introduces tensions.

- Lack of specific pedagogies in this zone not exclusive to this domain: given Rogoff’s perspective, and research on PBL approaches , (flexible - explain) frameworks are useful. While this review has identifies some, more are useful.

- Structural challenges continue but the stuggle continues: schools, curriculum etc, financial sustainability, limits of sustained volunteer activities, - however change is possible, this research provides a possible avenue.

Regarding game design patters, in the work of Werner et al [-@werner2014using], game mechanics are seen as a higher end of a computational sophistication framework, due to skill needed to assemble the component elements. My research instead asks how the similar packaging up of components into GDPs can be used as a navigational and content delivery mechanism.

The problem statement of the thesis

This section gives a further overall synthesis of the problems of the area based on Lit review that this study aims to address via the RQs.

From the reviews of the field above, it is clear that game making processes in informal settings can benefit from more research involving novel pedagogies designed to develop learner agency and identity as game makers.

In addition, the lack of pedagogical detail in existing research, particularly of which are communicated in a detailed and robust way, suggests that the research process should be outlined in a way which allows replication. This need aligns with my own commitment to and experience in documenting learning processes and facilitation materials in an open source way.

My final research questions involves the development of agency. This focus guides both the way in which I review current research on game making pedagogies, and how I describe current responses to current limits to the potential of game making in the final part of the chapter.

pedagogies exist but more are needed

Lack of specific pedagogies (for informal spaces) - via a case study / research ?

The lack of pedagogies for informal spaces should be addressed.

While the very open ended approach of build a space and response to the interests of people that come is attractive [see Denner], it presents challenges.

Similarly vehicle like competitions come with some support but also with issues []

These are explored in the next section of the LR

There is a missing

Link to the next chapter

Having explored the remit of the problem statement, and the body of literature relevant to this domain, we can see that a research approach which allows for a detailed exploration of both context, pedagogy and learner agency is required. In the following chapter I outline the approach of the study to achieve these goals based on the principle theoretical framework of activity theory.

Holding Zone / For the Chop?

Barriers to participation in game making practices (explored in contextual settings)

This section review existing research on digital making to identify barriers to participation in digital making and in particular coding practices in key contexts.

While the primary focus of this thesis is on an emerging coding community in a non-formal learning environment, the wider implications and learners should be applicable in school settings. There are however existing institutional barriers to this happening in traditional school classrooms. To address this, the next section explores these barriers in a UK context of computing and digital skills school-based education.

Institutional Barriers - related to UK School context

- Change of exam in to computing in 2014

A change driven by x

A section on the promise of the curriculum, and the hobby based activities created by individuals and non-profits to support project based work. However, in 201X, the coursework element of GSCE exam, which allowed students to engage with hands on coding, was rapidly removed due to student accessing ‘worked examples’ of code solutions online and incorporating them into their.

As students are able to write in psuedo code this means

Technical Barriers - Difficulties in learning to program

Summary here [@gomes2007learning] [@joao_cross-analysis_2019]. and here

<!-- Through a literature review on this topic, we aim to organize and systematize the main difficulties into four dimensions of analysis: (i) subject and complexity of languages; (ii) technologies and applications; (iii) teachers and teaching methodologies; and (iv) pupils’ skills[@joao_cross-analysis_2019] -->

In particular, the dilemma between more authentic languages and block based approaches [@joao_cross-analysis_2019].

More literature which examines the complexity of language and development environments should be found here.

Complexity of syntax and problem of leading with syntax [@gomes2007learning]

Issues of needing levels of abstraction in learning programming [@gomes2007learning].

Specialist coding tools and computational kits

There may software and hardware kits aimed at novice coders and in particular younger audience [@yu_survey_2018].

This section briefly summarises some of the adaptation in particular, that software has undergone to adapt to this audience.

Much work has been taken out by MIT family developing Papert’s ideas on constructionism in tool use

- Block coding vs text coding, syntax

- Design principles for game making tools, [@kafai_connected_2016; @resnick_reflections_2005] ()

- Barriers in using support material for code examples- mapping, understanding, [@wang_novices_2021]

Scratch and GSM merit particular examination as mini-case studies. The

- Scratch and community element.

- Remix as a feature: [@amanullah_evaluating_2019]

- Online log in

- library of assets to speed up creation

- In built asset authoring tools.

Game star Mechanic added quest ability, and a narrative set in a steam punk aesthetic. Of interest to this study are the motivational use of narrative, and accompanying resources which help analysis of game design patterns and systems based challenges.

NOTE - referenced in design chapter - the alignment with the use of code playground and template.

Computing syntax Lack of knowledge of what to design.. which they call “sandbox games,” that integrates the worlds”

Cultural / Identity barriers to participation in …

Barriers to participation

Develop from introduction, move to a overview of literature which addresses barriers in participation in coding communities from literature.

The focus of this review is to identify broad streams and currents in research.

Barrier - Identity and computer cultures

Early work from Papert and Turkle addresses cultural barriers to computing culture [-@papert_epistemological_1990]. The distinction between hard and soft approaches to learning is explored particularly in studies refuting conceptions that there is a right way to do computer coding. In this context, the hard approach infers a top-down perspective, highlighting advance planning and logical deconstruction of large problems. Papert and Turkle identify the privileging of abstract thinking over concrete approaches in classroom teaching a tendency which is mirrored by recent conceptions and advancement of computational thinking as teaching ideology [@wing_computational_2008].

Paper and Turkle locate different, softer but equally effective coding strategies. Soft coding suggests a more immediate and learner-directed connection with the materials or digital artefacts involved. The learner is presented as adapting a familiar set of concepts and processes to new situations and challenges as they arise as a ‘tinker’ might use well worn tools to skilfully bodge a repair job [@papert_childrens_1993, p. 143].

Kafai and Peppler also address the issues of gender identities and game design [@kafai_beyond_2014] asking how to create new communities and learning environments which align with values of participants rather than aiming to break into existing ones. They propose that we ask not How can we bring girls into the game making clubhouse but rather How can we build new clubhouses suitable for the interests of girls. Two of the playful elements they suggest are textiles related technology and the promotion of more collaborative online spaces as opposed to technology competitions.

Barrier - unfamiliarity with support practices

While home education support practices of families are expressed in this setting, a computing context requires specific support techniques that may be unfamiliar to parents [@roque_engaging_nodate; @roque_becoming_2018].

Outlining cultural barriers / aspects of game making

The following studies are explored future in LR. Here I surface cultural barriers experienced by participants.

Gender related identities

- Important to caution against gender stereo-typing and identity in relation to computers [@pelletier_gaming_2008]

- study by Fisher and Jenson critically explored diverse themes through a summer game making programme 2017). Emerging issues included pinkification, marginalisation and exclusions of women from game cultures, sexualisation and harassment.

Race related identities

In study by Thayter and Ko [@thayer_barriers_2017] the work of Margolis et al is analysed using concepts from communities of practice, type of barriers, and personal obstacles [@margolis_stuck_2008;]

Stuck in the Shallow End: Education, Race and Computing by Margolis, Estrella, et al. [ 12] examined the racial gap in high school CS, finding barriers that included lack of access to classes (formal boundary), cultural expectations on who the classes were for, feelings of isolation in classes, divisions within classes between those who “have it or don’t have it” (informal boundaries), and lack of social support(personal obstacle). Additional studies found participation and success in computing programs depended on background experience [ 2, 27 ], comfort level [ 27 ], sense of belonging and stereotypes (dis proportionately negatively affecting women) [ 2 , 5, 10, 16 ], view of self as an “insider” [21], and believed role of luck [27]

Glitch game testers [@disalvo_saving_2014; @disalvo_glitch_2009-1; @disalvo_learning_2008]

Outro

Illingworth critique’s Kafai and Burke’s book due to lack of specificity in the game making techniques outlined. This is particularly the case in chapter x which explores cultural elements of game making research. In recent years the constructionist school has taken care to start to describe cultural elements of learning environments [EVIDENCE]. Other approaches exist - AT etc .

Game making and coding and in schools and formal education

The most prominent learning objective of making games in educational setting is to develop coding and computing skills. There are extensive studies on game making to learn other subjects including maths, biology and chemistry but diverse examples exist. Game making can also develop social skills, self-reflection, cultural awareness and a range of technical abilities that allow participation in information society.

They are also a powerful vehicle for exploring issues involving race, sex, social issues [@tekinbas_quest_2010].

While there has been a large body of research on the value and practice of game making for educational purposes, it is a dynamic landscape which has many areas which merit additional research.

The context of many studies of game making to learning either computer science or other subject knowledge in curricular for the most part happens in a school or after school environment.

Coding and Computing as a School Subject in the UK

The influential report “Next Gen: Transforming the UK into the world’s leading talent hub for the video games and visual effects industries” was focused on providing the UK games and animation industry with the talent needed to succeed [@livingstone_next_2011]. The top recommendations were to include computer science in core curriculum, introduce a new Computing GCSE (a general exam for 16 year olds before they progress to more specialised study) exam, offer bursaries for computing teachers and to implement well-supported use of games and visual animation in the school curriculum as a way to attract more young people to the subject.

- New curriculum

- bursaries

- CPD

- CAS and community responses

- tapping into the enthusiast maker culture

Finance models for promoting Computing in Schools

STEM Learning NCCE - teachcomputing.org - How did this develop?

Reduction in grass roots responses. And less of a focus on directly teaching pedagogy. More meta in approaches.

CAS are supported by BCS and direct help from gov? The grass roots resource creation .

Raspberry Pi foundation have incorporated previously independent organisations Code Club and Coder Dojo and Raspberry Jam which mobilised volunteers to devliver a grass-roots enthusiast events.

Financial elements in general, lack of specialist funding addressed by training CPD funding for schools. But the effectiveness of this is limited in teh following ways. Time, enthusiasm,

Games in Schools

The After the Reboot report [@waite_pedagogy_2017], returned to the subject of game making as a way of increasing engagement in the process of coding. The review highlighted several areas of promise which needed more research: using games for engagement, use of design patterns - a term explored later in this chapter - and the involvement of girls in coding and social and cultural aspects of coding. The “After the Reboot” report also contained concerning observations. The report found that girls, ethnic minorities, and students of lower socio-economic status were all less likely to take computing as a subject at GCSE level. Game making aligns well with the principles of inclusive practices and project-based learning (PBL). It provides: learner choice in projects which increases motivation; authentic and shareable project outcomes to encourage peer feedback and reflection; iterative projects work supporting student mastery; and challenging goals and guidance in goal setting aiding self-regulation in learners.

Context of game making and wider digital making and culture home and informal settings

The context of informal communities is important to situate in summary.

Making games that will be played by audience of friends and family and using tools used beyond the scope of education, professional communities.

In this study the focus on historical and cultural artefacts and practices brought by Rogoff, and in particular the concept of guided participation, originated in non-school settings, is helpful.

On games as a home and informal culture

The work of Livingstone is foundational in the area of home learning of digital technologies [@livingstone_digital_2018] uncovering a rich repertoire concepts and practices that families may bring into a non-formal game making process.

Retro gaming has a place in our society’s public memory [@heineman2014public]. For this study I use a definition of early arcade games from the 1970s and early 1980s and early generation of home consoles before the advent of 3D graphics. Retro games have a particular aesthetic driven by graphical limitations and the simplified game mechanics which are due to the limited capabilities of the hardware and storage space involved.

Ito’s work on and naturalistic studies of digital use and creativity in the home including the value of informal playing around [@ito_connected_2013-1; @ito_hanging_2010], and Gee and the process of tapping into affinity groups and affinity spaces [@gee_what_2004]. Gee’s (2004b) work on games and associated culture as learning experiences is founded on his understanding of how the engender a shared discourse and emerging identities.

In addition, maker culture more generally is relevant due to the alignment with tinkering as educational practice in stem education, supported by family involvement and brokering of experiences. The details of tinkering as a pedagogical practice are explored in more detail in the literature review of this thesis.

Casual and retro games played by both adults and children are increasingly available via smart phones and home consoles. The nostalgia around such games and the associated aesthetics of cuteness creates a potential for connection between younger and older players [@boyle_retro-futurism_2017]. The sustained popularity of retro games together with easy-to-use game making tools and code frameworks provides an entry point for game players into game making cultures which is reflected in the success of amateur games publishing websites like itch.io [@garda_nostalgia_2014].

Building on the concept of participatory culture [@jenkins_confronting_2009], where x and y, there are several streams of activity that are important to reference as foundational context for this study.

Context of Home Education and family learning

NOTE SEE THIS SUMMARY - WHICH MUST BE IN HERE SOMEWHERE TOO - https://docs.google.com/document/d/1grMat_sXRLdlRSDtR17Lyxf1OAg3ZpOxTWfnDZ3kkIU/edit

The move to family learning as a context suited the trajectory of my interests and the opportunities available as part of University context.

Many professional programmers began with support provided by family.

Barron and Livingstone have outlined the advantages and processes involved in family involvement of technology use and learning in the home.

There is clearly an inequality of access to these well paid profession that the development of the computing curriculum and the skills based and creative process focus that was part of the initial narrative is laudable the aims of equality.

However the practical and and cultural difficulties of undertaking a project-based approach within the curriculum are significant. Factors of difficulties associated with technology projects compound difficulties.

In this research I made the decisions not to focus on the adaptation of a informal club approach to the restrictions of in-school classes but rather instead to embrace key elements of it and to explore processes in situ My involvement with home ed networks stemmed from University outreach work.

While the context of home education is not a core to the goals of this research it is important to situate this study accurately.

Outline of the home eduction context of this study: The processes and motivations driving of home education are varied [@fensham-smith_invisible_2021]. Classic ideas of reasons for HE include pedagogy and ideology [@galen_home_1991] [@rothermel_can_2003], and often both.

- Unschooling, Holt, drawing out interests of children in everyday activities and facilitating learning around that [@gray_challenges_2013]

- Webs of learning Illich - home ed families active in identifying networks to tap into [@doroudi_relevance_2023] has a relevance with social networking groups and email lists used by home educators to share and align activities.

Game making and maker culture in non-formal learning contexts and third spaces

Physical spaces which suit non-formal approaches

Much research on game making focused on non-class room settings.

For example Papert’s work

Digital learning in IILP (GLAM settings) is fertile [@degner_digital_2022; @schwan_understanding_2014]

An area of tension to address - limited leaner choice in process if driven by curriculum.

Authors note that UMC and the value of project based exploration can clash with classroom culture driven by curriculum goals.