2. Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Research Questions - October 2023

- To perhaps add to Lit REVIEW

- Literature Review Introduction

- Pedagogies from coding for learning community - K12 focused

- Pedagogies for informal settings

- Pedagogical resources in the form of professional practices and frameworks

- Synthesis of chapter / discussion

- The problem statement of the thesis

- Theoretical Framework

- Currently Parked from Literature REVIEW

Literature Review

Research Questions - April 2024

~1. What pedagogical tools and processes are available to support novices to overcome barriers to participation in game coding processes?~

- What ~barriers~ contradictions arose in participation in this research’s game coding processes and what pedagogical tools and processes are available to address these contradictions?

- How can game design patterns support the development of coding practices with novices?

- How can learners build agency in an evolving community of game makers?

To perhaps add to Lit REVIEW

- Hands on Education - what is it? Examples in STEM context[@holstermann_hands-activities_2010].

Literature Review Introduction

The aims of this literature review:

- Recap motivations for game making and terms needed to expore that later

- CT in relation to Design Patterns - abstract / concrete elements

- outline existing game making pedagogies & resources for learning coding

- focus in on cultural / social elements of particular promising pedagogies.

- Theoretical Framework - introduce concepts that may also inform conceptual framework

Structuring the literature review

To help answer RQ1 and 2, this literature review explores pedagogies and resources used by practitioners and learners to support the process of learning

Specifically in RQ1 terms - what does authentic mean. A bit of what does agency mean which is followed in chapter three.

Identify types of barriers / obstacles and address pedagogies which address then? Because of the community focus of the study, but the relevance of new curriculum the lit review spans different community perspectives / scopes.

- What is learner agency

- definitions of agency and education

- what is agency in this context?

-

Coverage of wider pedagogical frameworks focused on participants to develop agency in an evolving community.

- what is informal settings / learning?

- communities of practice - legitimate peripheral participation boundaries and Barriers

- community of learner and the methods to expose practice

-

Examples informal community creation in practice and research & pedogogies with young people

- Tinkering -Design-based & Tinkering / Exploratory - Bevan et al

- Parents as brokers in tech use / learning - Roque et al, Barron, Correa

- 5th dimension

- Mantle of the Expert (and drama processes games)

- K12 context: types of barriers addressed focused around curriculum and assessment, end with analysis of what formal ed often fails to address

- computational thinking vs coding practices: explain why CT not the focus, abstract / concrete aspsect.

- professional and enthusiast game making communities and informal setttings: better to address coding practices not -hci and affordance theory, technical barriers , solved by design - MDA - design patterns and gdp collections - game jam, playful approaches, drama games

The study then seeks to reconsile some of the different elements above in the context of family / informal ed -

- Theoretical Framework

What is a pedagogy?

One of the main themes of this review is to address what pedagogies are available in to help coding, in relation to RQ1.

It is therefore useful to disambiguate C in this context.

In AT terms pedagogy can be reframed as pedagogical tools and processes and can be viewed as a kind of mediational strategy.

Pedagogies from coding for learning community - K12 focused

There is a lot of similarity of game making pedagogies and that of digital making and broader study of media literacy. This section attempts to stay focused on game making where possible but widens domain if relevant to the questions of community approaches.

- Broader definition of CT, computational fluency / computational participation.

- UMC / Remixing - Half-baked games

Also See this writing and adapt

chapters/planning/lit review/game making/overview of gamemaking studies part one/overview_of_gamemaking_studies_v6 (002) + CL.docx.md

Definitions of Computational Thinking

The promotion of Computational Thinking (CT) has been a key factor in the development of the UK’s computing curriculum. However, the claims of early advocates that CT skills could be applied widely in subjects beyond computing are now advanced more cautiously to avoid the danger of over-promising [@tedre_long_2016]. We can use the distinction between concrete and abstract to examine the differences between two popular interpretations of Computational Thinking (CT). The first is an influential take from Jeanette Wing. “The most important and high-level thought process in computational thinking is the abstraction process. Abstraction is used in defining patterns, generalizing from instances, and parameterization” [@wing2011research]. Many learning resources designed to support the computing curriculum present this principle as four key pillars of CT: decomposition, pattern recognition, abstraction and algorithmic thinking [@bbc_bitesize_introduction_nodate]. The essence here is to deal with concepts and principles as abstract and separate from the context of coding.

Another widely used definition of CT by Brennan and Resnick [-@brennan_new_2012] was developed in response to a thought experiment “How do we describe what Tim, Shannon, and Renita are learning as they participate as designers of interactive media with Scratch?”. The researchers took a grounded / situated approach to mapping the potential learning dimensions of students designing and coding collaborative, creative computing projects. The resulting map they created includes computational concepts, computational practices and computational perspectives.

- Computational concepts include sequences, loops, parallelism, events, conditionals, operators, and data; thus representing the mechanics of coding structures.

- Computational practices include debugging, iteration, reuse and remixing, and abstracting and taking a modular approach.

- Computational perspectives such as expressing, questioning connecting were observed in the behaviour of learners completing their coding designs.

This interpretation of CT, based on observation of learners in action, is more accessible to teachers and learners as they can more easily recognise their own practice than in the more abstract interpretations of CT. To give a specific example, rather than decomposition, the applied framework outlines taking an iterative, incremental approach to problem solving and arranging code in modules.

This broader, process driven definition of CT has been used and adapted by many organisations seeking to support the new computing curriculum. As such, it may be familiar from websites, posters and other supporting material created by groups like Barefoot computing. Lye’s extensive review of teaching Computational Thinking [@lye_review_2014] used Resnick and Brennan’s definition as the basis for the review, which points to the widespread use of this more applied approach. The wider definition of CT here assumes an environment where learners are engaged in the collaborative coding of a computing project. The review above and the influential framework used by Computing at School [@csizmadia_computational_2015-1] have included elements of this applied framework as well as other more abstract CT concepts.

Can CT be used as an pedagogical framework

NOTE - PARTS OF THIS WILL LIVE IN LIT REVIEW.

The term abstraction has varied interpretation even within the field of computer science education [@hazzan_reducing_2002]. Papert and Turkle’s [-@papert_epistemological_1990] encourage a of diversity in approaches to teaching coding beyond a formal, abstract approach “that emphasizes control and through structure and planning”. Their celebration of concrete coding approaches, including the use of tangible physical and digital objects, and more piecemeal, bricolage approach has influenced the design of popular educational programming software and pedagogy through the constructionist school and maker movements (as explored in the literature review). In a challenge to this article Wilensky [-@wilensky1991abstract] questions the nature of abstract in this context arguing that all objects and concepts are abstract until familiarity makes them more concrete to the user.

Tedre and Denning’s [-@tedre_long_2016] review of CT cautions against a too narrow definition of CT that highlights formal abstractions as represented by Wing’s take on CT [-@wing_computational_2008]. This is not to argue that Wing’s approach to CT is without technical merit [@lodi_computational_2021], rather that its adoption by educational bodies like CAS in the UK and similar bodies internationally has risks. The inclusion of formal CT frameworks in curriculum and formal testing has provoked mechanistic teaching of decontextualised concepts via formal teaching methods to the detriment of hands-on exploration and creation of personally meaningful projects [@resnick_coding_2020].

In teaching computing pedagogy the concept of levels of abstraction can be taught to students to help them understand the level of abstraction that they are working at [@statter_teaching_2016; @waite_abstraction_2016; @waite_abstraction_2018-1]. To quickly review LOA, the levels are Problem, Design, Code, Running the Code. And the purpose is, “Levels of abstraction has been interpreted as a hierarchy to enable teachers and learners to describe which level they are working at, rather than as a methodology for programming projects.”[@waite_abstraction_2018]

Semantic Profiles and Waves

CT instruction can be aided with a focus of teachers on semantic profiles and waves.

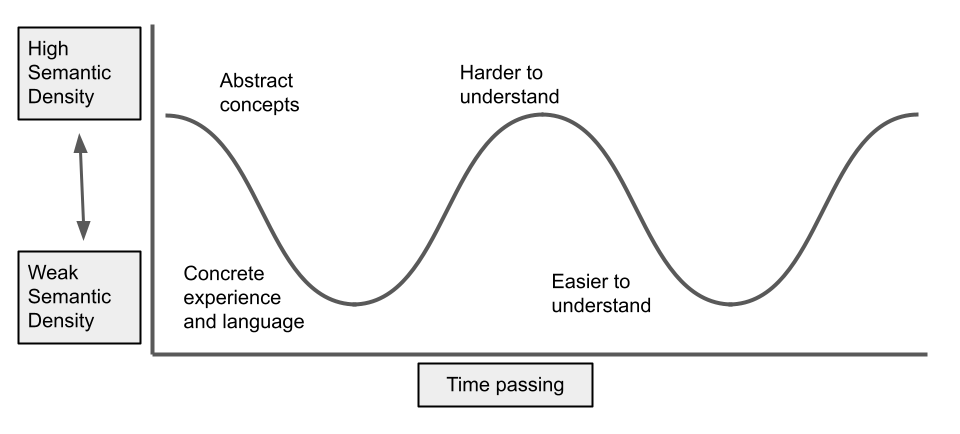

Semantic profiles chart the use of more concrete (high semantic gravity) language and more abstract (high semantic density) concepts and patterns as they emerge in classroom situations [@macnaught_jointly_2013]. Exploring semantic profiles is being promoted by NCCE an aid to teachers wanting to plan their lessons in a way that communicates the key abstract curriculum knowledge that students will need for exams, and to also allow them to put the concepts into practice to build real coding skills and to make valuable connections to personal experience. A Quick Read on semantic profiles is available on the NCCE website.[^2]

Research carried out by Curzon and colleagues [-@curzon_using_2020] in a computing education context outlines the value of semantic profiles in wave shape as opposed to a flatline which remains too much in concrete examples or more abstract concepts. This research highlights the value of unpacking, exploring and then repacking ideas during the course of a lesson. A student’s understanding of a concept may deepen a little bit each time it is applied in practice and then reconnected with the abstract.

Figure 3.1 A Semantic Profile with Semantic Waves

Examples showing semantic wave profiles usually start with the process beginning with the abstract or with high semantic density. See Figure 1.1 for an example. The advice of starting with more abstract terminology and concepts may seem to be in opposition to the approach of Concreteness Fading as explained with the CRA method outlined above. However, on examination of the research example carried out in the research above, the process of starting with concepts may only involve giving a short outline of the concept that is being explored and saying that this will be illustrated in a following concrete activity.

Exploring the territory between instruction-based tutorials and unguided approaches

The process of learning technical skills through trial and error is something that many self-driven learners are familiar with. The desire to complete a particular project and self-motivated access to the resources to achieve it is the stuff of computing mythology, recalling the kind of garage innovation that created Apple computer and early hacker computing culture [@fuller_garage_2015]. However, this is not an ideal pedagogy. Even with access to resources and critiques of pure discovery learning are also valid [@mayer_should_2004].

On the other end of the spectrum, tutorials are a common way of learning coding and exist in many forms and formats [@head_composing_2020; @kim_pedagogical_2017].

Code snippets are often interwoven with text explaining the function of the code constructions.

The variety of audience and motivations of writer can account for the variation in form. Researcher also point out the limits of online coding tutorials namely that: “few explain when and why a particular concept is useful in programming; and few provide guidance for common errors” [@kim_pedagogical_2017, p. 325].

Critique of instruction…

In short there are concerns with reproduction of information as a goal for varied reason but authenticity of experience and resulting negative on effects on motivation and participant agency are of particular relevance to this study.

What pedagogies support learner agency?

This section covers pedagogies more aligned with developing agency. This needs clarification

It was originally focused only informal settings, which offer advantages for developing agency in terms of having less restrictions.

NOTES remaining. ADD IN SECTIONS IF RELEVANT / AND OR TIME / SPACE

- Design approaches - designing for an audience

- Physical methods, feedback, from constructionism

- Design patterns in Agent sheets

Use Modify Create

The ‘Use-Modify-Create’ approach proposed by Lee and colleagues [-@lee_computational_2011] is particularly promising to counter issue of user anxiety and demotivation surrounding the difficulty of coding games. UMC evolved from research involving the use of game making and robotics to support computational thinking [@denner_computer_2012; @denner_using_2014; @werner_pair_2013; @werner_children_2014]. The model advocates the remixing of existing games to act as a scaffold to build the competence of the beginner coder. Learners are guided to progress in the complexity of their modifications, thus becoming increasing proficient in the recognition and use of computational concepts and structures [-@lee_computational_2011]

Use: In the Use stage, coders build a familiarity with coding interfaces, code structures and syntax through scaffolded approaches which involve interacting with the program code and what it produces.

Modify: In the Modify stage learners progress to working on real projects created by others. Learners deepen their knowledge of coding structures and practices by altering existing projects and templates to suit their own aims.

Create: After novice coders become more familiar with patterns of code design in use in the modify stage, they can progress to replicate such patterns in other code that they create from scratch.

A study involving five hundred 9 to 14 year-olds found that the UMC approach can balance a structured approach with more student-led exploration [@franklin_analysis_2020]. The researchers also found that the students enjoyed the UMC approach as they had more choice and agency in the process. This is supported by other research which compared UMC with a starting-from-scratch approach and found higher student engagement for those in the UMC group [@lytle_use_2019]. The researchers found that because students using UMC had more time to play around with code, they were able to add their own personal touches and that this ownership over the code sustained their continued engagement. While the scope of the study is limited, observations support motivation of UMC that this pattern of creation maintains higher level of engagement through reducing technical barriers to participation, and affording greater sense of learner’s ownership over end project through greater choice over the final outcome.

Research on UMC which develops learner choice

UMC has been developed to be end with scaffolded set of choices. In a study where students use a block based language to develop simulations - the authors note limits of study but are enthusiastic about providing a limited set of choices for final exploration within a limited time frame [@lytle_use_2019-1; @lytle_use_2019]

- Scaffold Students and Teachers- Providing the necessary programming blocks students need to complete a choice

- Differentiate Choices by Difficulty - create choice systems that have varying difficulty

- Create Choices that Show Visible and Immediate Changes

- Make things Complex, not Complicated

- Draw from Student Desires - students will engage more with the material, feeling like the creations are their own.

PRIMM

FIND MATERIAL IN OTHER BOOK CHAPTERS

PRIMM: PRIMM stands for Predict, Run, Investigate, Modify and Make. This model helps learners adopt coding practices and computational concepts through providing a concrete code example that they run after predicting what it does. Learners make changes to the existing code before finally creating code from scratch. PRIMM’s starting point is students predicting existing code results. Asking students to identify target computing concepts in code examples allows teachers to guide students towards key computational thinking process or algorithmic details. Thus, PRIMM is well suited to the classroom as starting with prediction of a code allows a whole class of learners to unpack and repack the same set of concepts in a restricted time scale. This process that supports formal problem solving, paper-based questions of the GCSE exams. The use of code examples and a structured set of varied activities aligns well to UDL principle of representing knowledge in a variety of means. For a more detailed summary of the PRIMM approach the Quick Read pedagogy article.[^5]

Primm based on UMC but developed to highlight abstract concepts and processes via a predict stage.

Microworlds as an embodiment of UMC and other constructionist design principles

LOGO and Scratch have had a huge influence as have the constructionist design principles

The main concept of UMC is remixing a game to build . Scratch has been instrumental in bringing this methodology into clubs and classrooms as an explicit feature of its online community.

Constructionist design principles emerge in tandem with the frequent revision of the tools in question in response to the direction and interest of the community. This form of praxis is illustrated in a good level of detail in Papert’s extensive pedagogical writings and the community of researchers and educators clustered around development of scratch and associated pedagogies.

Constructionist design principles

The development of Logo as a programming language moved towards the use of block coding under the stewardship of MIT labs.

Resnick’s work on constructionist design principles via software and tinkering tools merits summary here. CF - introduction.

Papert’s concept of microworlds refers to simplified computer simulations or models that provide a controlled environment in which students can explore and experiment with maths or physics concepts in a concrete way [@harel_constructionism:_1991; @papert_mindstorms:_1980; @papert_childrens_1993].

Papert believed that microworlds were an effective tool for promoting computational thinking. His take on CT however, should be contrasted to a abstracted later take from Wing [@lodi_computational_2021]. Instead here CT concepts are heuristics developed from concrete experience.

This concept of CT as a set of heuristics or design behaviours continues in practitioner-focused interpretations of CT.

MOVE TO LR There is research on computing projects in the work of Papert [-@papert_mindstorms_1980] on Mircoworlds and subsequent research on programming tools in the constructionist tradition [@kafai_constructionism_1996-1; @kafai_mindstorms_2014].

Papert argued that microworlds could help students develop computational thinking skills by providing them with opportunities to experiment with computational processes and to reflect on their own thinking. In addition to the software based tool of the microworld, the social context is key to the whole process.

While, examples of a Microworlds are diverse [@rieber_microworlds_2004], a Turtle drawing world using LOGO can be used here as an example. In the Mathland of the turtle which speaks only LOGO, children are drawn to speak LOGO to progress. The affordances of the physical turtle provide visible motivation.

He argued that by working with microworlds, students could engage in hands-on and minds-on learning, which would help them to develop a deeper and more meaningful understanding of the concepts they were studying.

The work of Papert and the concept of microworlds continue to be influential in the field of educational technology [@kafai_constructionism_1996-1].

Today, microworlds are used in a variety of educational settings, from primary schools, afterschool clubs and universities. However, the use of microworlds in traditional school settings is not unproblematic [@papert_turtles_2002]. There is a danger that the potential is ‘trivialised’[@hoyles_microworldsschoolworlds_1993] into a vehicle for instruction based processes aimed narrowed to teacher chosen curricular concepts.

Half-baked games as Microworlds

The concept of ‘half-baked’ games, which are incomplete or somehow deficient in a way which motivates learners to delve into the code and improve them offers a possible enchancement to the ‘Use-Modify-Create’ model []

This concept of builds on Papert’s concept of micro world used a framework for making and coding.

The focus of half-baked games is to design them in a way which encourages malleability of the code in directions that the learner may find interesting [@kynigos_half-baked_2007; @kynigos_children_2018]. Thus the original game designer makes complex decisions which highlight certain affordances of the game in a way which encourages the exploration of key concepts, in this case computational thinking.

Kynigos and Yiannoutsou identify a progression in the type of CT skills being used as the processing of modifying the game progresses as part of the Use-Modify-Create model moving from elements like pattern recognition associated with reading of code to ones like a creating abstracted structures and sequencing their own algorithms. Kynigos also highlights the possibilities of half-baked artefacts to build learner dialogue around the problems at hand as as ‘a communicational tool to shape a common language within the community’ 2007, p. 336).

Funds of knowledge and third space

Studies using funds of knowledge within their pedagogies

Listed in this section are numerous studies looking into the use of home interests in coding process. For example in domain areas of wearable technology and fabric, storytelling, robot making and games.

The concept of funds of knowledge is outlined here in brief form. Include Moll here. And followed by key observations supporting the importance of expression, of feelings of expertise, and some pedagogical techniques tactics to

Third spaces and the context of this study

The concept of third space is helpful in the context of this study in particular as a space between home life and formal education.

It also is rooted in a sociocultural understanding of learning that is challenging to traditional classroom environments.

Play circles and MOE as a third space

The concept arose in research of this PhD, however it resonated with my past work on forum theatre, art activism and performant art.

A foundation of link between between play theory, MOE and third space theory.

A detailed analysis is beyond remit of this review but broad alignments include:

- use of concept of a new creative space for all participants

- use of mediated strategies to reduce learner stress

- ability to bring self identify to share in a scaffolded and protected way

Pair programming & social/collaborative coding

Pair Programming: Pair Programming groups students in pairs and divide coding two into two roles. One student undertakes hands-on coding while the other is free to think about more the abstract design of the overall program. A benefit of pair programming is to increase coding confidence as students build their experience of the different roles involved in coding. To help novice coders teachers should model and break down the processes involved. Pair programming involves social learning elements and can model a greater choices for students in they way they solve problems. The process of building an identity in a community with the help of peers is key to a socio-cultural understanding of how learners pick up coding in a classroom (or other settings). The importance of a coding community is explored in another chapter in this collection on design and project approaches. A summary of pair programming roles and tips on how teachers can help learners to adopt them in present in a Quick Read document from NCCE.[^6]

See Robertson

Bring in limits and extension of research on pair programming to wider groups / more flexible processes [@preston_using_2006] -

Concepts - perhaps some of the underlying concepts like

- joint problem spaces

- resource interdependence from Preston

Digital informal / participatory culture and Learning

Tinkering and Constructionism Livingstone Sefton green ITO and Gee

community activities around the game Gee / Ito

Project based learning PBL

NOTE - This spans k12 and more informal / community environments - thus I’m not sure where to place it at the moment - Lit review needs reworking.

Project-approaches are widely advocated by Papert via constructionism school and taken up by MIT researchers and programmes, especially the outreach work of Mitchell Resnick surrounding Scratch and other creative computing project.

PBL also aligns with a much broader progressive approach to education. The broad benefits can be summarised as such;

- Student choice

Cautionary note While the above claims are widely supported, the wide nature of the definition complicates any broad claims of replicability.

Game making and Project / Problem Based Learning

Game making can be seen as an example of the kind of wicked problem favoured in project-oriented problem based learning (referred to from now on as PBL) (Mateas and Stern, 2005). PBL has a variety of forms, an exploration of which is beyond the scope of this study (Aditomo et al., 2013). The most pertinent areas of PBL of to this study are the over-arching focus on authentic learning environments and the process of building learner autonomy within a structured and supportive approach [@hernandez_aalborg_2015]

When learners undertake real life projects with relevance for, or with a direct link to, environments outside of the learning space, there are strong parallels to the models of peripheral participation in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998). A PBL game making process would do well to foster participation by highlighting playful paths into community participation to maximise group identification and sustainability (Thorsted et al., 2015). Fictional tasks and roles can also impact learner engagement (Heathcote and Herbert, 1985).

The structuring of the learning involved in PBL is highlighted by those wishing to defend it from dismissal as unsupported, pure discovery learning (Hmelo-Silver et al., 2007; Kirschner et al., 2006). We can see parallels in PBL programme design to that tinkering tools and environments in that decisions are made to support specific areas of learner discovery deemed of particular value by carefully obscuring other potentially distracting aspects behind ‘black box’ processes (Resnick and Silverman, 2005). OTHER HEURISTICS OF CONSTRUCTIONISM

I propose that there guidance and tactics in area of discovery based learning to help balance between learner choice and engaging, open experimentation verses steering towards useful shared concepts is often under explored in research leaving a documentation gap that .

Why does this gap exist? Partly due to the compressed form of academic papers, partly due to the privileging of abstract analysis over more domain specific observations on practice.

PBL and Authenticity in the domain of teaching programming

The goal of authenticity of expression, assessment and the motivation of a real audience aligns PBL with the kind of learning that happens when people take part in work-place or other authentic activities.

There are overlapping dimensions and spectrum of authenticity in learning environments including; hands-on experimentation (as opposed to text-book sources); proximity to workplace practices and professional tools; personal relevance to learners.

While PBL has the potential to address all of these factors there is some ambiguity in much of the literature on PBL. EXAPAND WITH CRITICALITY. There is a lack of clear advice on how to ensure authenticity

In the domain of computer programming,

The next section deals with pedagogical approaches that are rooted in professional or non-educational settings.

Issues of Inclusion and PBL addressed through UDL principles

One way to address SEND issues is to use differentiation to adapt a the standard lesson plan for learners needing special support. However this view of a standard, optimal learner pathway is not supported by recent research in neurodiversity, which suggests there is no one optimal way for students to learn. Inclusive pedagogies take a different approach to differentiation which places more power in the hands of learners to choose the path that is most appropriate for them. All students are given a greater choice of materials and activities from the start suiting the varied needs of all students. This has the benefit of removing stigmatisation of some learners having to undertake work that seen to be created for low-achieving students. These principles - among others - are presented in a framework called Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

Rather than designing separate activities and support for learners with different educational needs in the classroom - often labelled accommodations for disability - UDL facilitates learners to choose a learning pathway that suits their individual abilities and learning strategies.

UDL places great value on the personal relevance, choice and authenticity of learning experiences. As a way to encourage engagement UDL suggests setting choices of concrete learning goals that are relevant to the learners. This learner-led approach is very different to a traditional-instruction based, directive approach to teaching. The diverse learning pathways offered can be unfamiliar for both teachers and for students. The UDL guidelines recognise this and provide information to support teachers to implement them. As educators, we may need to build our own abilities and familiarity with learner-led approaches as well as growing the autonomy of our students.

One area of UDL that teachers can implement straightforwardly is to represent concepts in the classroom in a diversity of ways. In a related study, researchers Cook and colleagues [@cook_using_2016] explored the alignment of UDL with another framework, CRA, which consists of a three stage model to support learners to develop concepts [@fyfe_concreteness_2014].

The researchers outline how the three stages of CRA (Concrete, Representational and Abstract) align with key UDL principles, most specifically multiple ways to represent knowledge to aid learner perception and comprehension. In short, first teachers introduce a physical, concrete model of the concept, then progress to iconic forms, for example graphics or pictures; finally learners work with more abstract models of the concept. The CRA framework is an example of concept popular in Mathematics research and practice called Concreteness Fading where concepts are introduced in concrete examples and then learners are supported to understand and represent them in more abstract ways.

When reading about different approaches to teaching computing the terms concrete and abstract are used commonly. For example the concrete practice of coding is a good way for learners to work with more abstract computing concepts. The following section explores the utility of these terms to explore inclusive approaches to teaching especially in relation to an understanding of Computational Thinking.

Pedagogical resources in the form of professional practices and frameworks

These professional practices and framework are both informed by research and in common use in professional communities.

Where there is overlap between domains this is explored in each section.

Design steps frameworks via stages

Many design frameworks exist in diverse areas of production with varied degrees of adoption. One stream in CS stems from engineering and design thinking [@mouza_imagining_2013; @resnick_all_2007; @winarno_steps_2020-1].

A typical framework from teach engineering website [@noauthor_engineering_nodate], takes the form of Ask: Identify the Need & Constraints; Research the Problem; Imagine: Develop Possible Solutions; Plan: Select a Promising Solution; Create: Build a Prototype; Test and Evaluate Prototype; and Improve: Redesign as Needed

This has been adapted by computing educators elements of are included in early literature to help adoption of new computing curriculum in UK [@csizmadia_computational_2015].

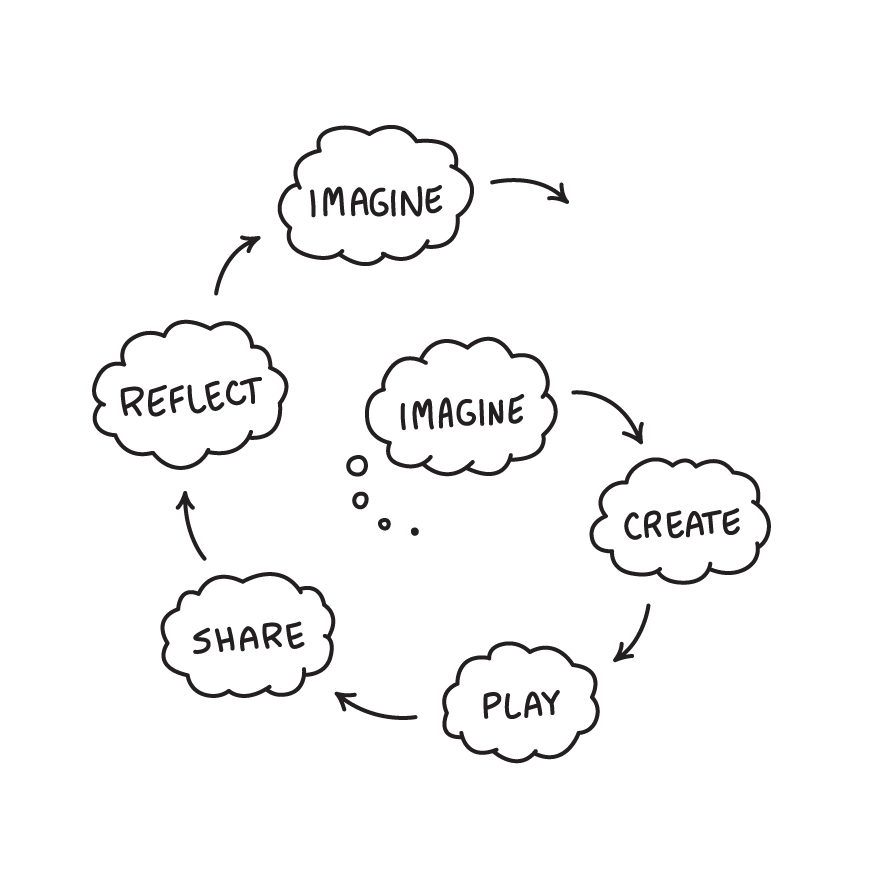

Michel Resnick, a researcher involved in the Scratch project at MIT illustrates an approach to design-based education through a creative cycle. The five circular stages are; Imagine, Create, Play, Share, Reflect and returning to Imagine once more. The model encourages both parents and teachers to create a supportive environment for creativity.

Figure 8.1. Diagram of five circular stages; Imagine - Create - Play - Share - Reflect - Imagine

There is less clarity about if and how the stages could be used by learners to scaffold their design process.

(critique of this in terms of writing structures stages at primary )

Broad design based approaches

Resnick [-@resnick_scratched_2012] describes the foundations of the design-based approaches in education as; engaging in design activities, exploring personally meaningful topics, collaborating with others, and deepening understanding through reflection. The key reason to adopt these principles is to increase engagement via sustained participation in computing projects for a broad range of learners. One of the sources for sustained engagement is when, as part of the iterative process, learners are able to test and then revise their creation or experiment based on their own evaluation. Another factor is the importance of a community in the design process, as a real audience for creations, as a source of inspiration and as peer evaluators in the testing process.

MDA and conceptual game elements framework

The MDA framework has been created from games research with an aim to help define

The Mechanics element of the framework has much in common with GDPs. The different is explored by researchers [@olsson2014conceptual].

The common element is the utility of the concepts to designers. Although the process of formalising such patterns and mechanics is also noted. The levels of abstraction of

Game jams & game competitions

Some of the tools that emerge allow participants to rapidly explore game concepts - See exercises on - space, mechanics, rules,

Hackathons, Game Jams and accelerated production methods

Hackathon events are characterise by a time constrained and thus accelerated production ethos. They have widened beyond code to embrace other creative and educational domains [@johnson_civic_2014; @kienzler_learning_2017]

The value of rapid prototyping has been popularised by Agile design techniques as a way to avoid wasted planning time. The theory being to create a minimal proof of concept and test with users.

Accelerated production methods are being applied to a wide variety of domains. Game jams draw on rapid prototyping processes, and from hackathons they add constraints to accelerate creativity [@arya_international_2013; @gabler2005prototype].

Game Jams are an a type of hackathon where participants create games individually or in teams in a time-constrained period, typically 24 or 48 hours. Team events often take place in physical venues which may be part of a wider global Jams [@arya_international_2013]. Within Game Jams a breadth of materials are used including video games, interactive fiction, and even a Cardboard Jam [@eberhardt_no_2016].

Eberhardt also identifies potentially incompatible strands of Game Jams, specifically citing commercialised events and professional Game Jammers contrasted to those Jams with a social purpose with a more diverse, less target driven audience [@eberhardt_no_2016, p. 3].

Goddard et al have analysed the key aspects of Game Games including tools, organisational processes and rewards systems [-@goddard_playful_2014], using a playful vs. gameful spectrum from Caillois [-@caillois_man_2001]. Relevant design factors include; allowing teams to register before the event or enforcing a more playful team creation process, varied award categories which encourage diverse outcomes rather than technically structured awards and the culture of the Jam which may encourage risk taking and experimental process over commercially viable products.

Beyond the scope of more competitive Game Jams a collective of New York educators have collaborated to create a process aimed at young people that can be applied in a shorter time-frame [@games_for_change_get_2017]. Their process, the Moveable Game Jam, emphasises low-cost and both digital and analogue offline game production. The motivation is to communicate fundamentals concepts of game design process to participants.

The Moveable Game Jam can be situated on the playful side of the spectrum in that it uses loosely structured activities and broad goals allowing for significant learner agency. Conversely, there are element of a more structured approaches in the steering of game outputs towards particular social goals, periodic facilitator checking of the fundamental concepts previously mentioned and the use of extensive playtesting in the process.

Play testing is the process of involving other participants to try out a prototype of a game early the creation process [@eladhari_design_2012]. It has a particular value in forcing an iterative approach.

GAME JAMS FOR NOVICE CODERS - SEE RECENT WORK

Jamming, a term common in music and theatre, describes responsive, improvised, rapid and fluid responses to collaborators ideas and audience reactions [@pinheiro2011creative; @sawyer_group_2003].

The area of improvisation is under explored in game jam context compared to that of music and theatre [@jaffurs_impact_2004-1; @merilainen_game_2020].

The alignment here with foundational game theory of the magic circle CITE []. The value of setting up playful learning environments has been explored in the context of bringing value of informal learning to environments of higher education WHITTON []. Benefits include, the reduction of learner stress, and creating a no wrong answer environment.

Design Patterns and Game Design Patterns in professional context

NOTE - I think there is material to copy and paste here.

Design patterns are most commonly used for computing students at higher education to teach object oriented computing but they are also useful for all levels of learners. Design patterns are rooted in real-life incidences of problems that are often solved in a particular way. They are concrete examples of coding principles in context.

Design patterns are most commonly used for computing students at higher education to teach object oriented computing but they are also useful for all levels of learners. Design patterns are rooted in real-life incidences of problems that are often solved in a particular way. They are concrete examples of coding principles in context. Design patterns can help the development of coding communities if more experiences coders take the time to document the patterns they use in an accessible way for novice coders. For educators the use of design patterns can help support learners develop coding proficiency by providing scaffolding and modelling good design decisions. However, one of the challenges for teachers of using worked examples and design patterns is how to integrate them into student-led design challenges.

The concept of computational design patterns is well explored in the professional literature of computer programming and design [@gamma_design_1995], and has also been adopted by game designers [@bjork_patterns_2005]. Design patterns are well thought out solutions to common issues faced by computer programmers and system designers.

Research in this area points to challenges of teaching the abstract nature of traditionally shared design patterns related to object oriented coding languages but points to visual methods and games as promising tactics [@azimullah_evaluating_2020; @da_cruz_silva_fostering_2019]

The term game design patterns (GDP) is used in different ways. Kreimeier [@kreimeier_case_nodate] distinguishes content patterns from software engineering patterns. Software engineering patterns are used to structure code and keep it architecturally neat thus facilitating code sharing and extension. These patterns would be invisible to the end player of the game. Content patterns describe common patterns of game play and design that are visible to the player.

Eriksson and colleagues [-@eriksson_using_2019] use the second interpretation rephrasing slightly as gameplay design patterns, thus placing emphasis on the exposure to the user via playing the game. They described the utility of games design patterns as a lingua franca for game developers. Other benefits cited are GDP as a source of creative inspiration and as an aid to problem-solving.

Their research, which involved young people, builds on related research with adults with the explicit goal of learning game design. One product of this research is a list of GDP patterns as a public collection (available at http://virt10.itu.chalmers.se/) [@bjork_patterns_2005].

MOVED TO LIT REVIEW FROM CHAPTER 5

In a design education intervention working with 11-12 year olds Eriksson and colleagues [@eriksson_using_2019] used a collection of curated patterns to prompt learners to analyse and then propose changes to an existing collaborative game called Stringforce. It is useful to compare the supports and approach of Eriksson’s Stringforce study with that of the 3M intervention of this study.

The overall goal of the analysis of GDPs also differ, in the 3M study the principle goal is analysis of the use of GDPs by learners to aid their goals in creating their own games. In Eriksson’s study the principle goals to is to address the perceived “challenge how to make results from research work related to this within Child-Computer Interaction (CCI) field easily transferable to future CCI research.” [@baykal_using_2019] The Stringforce study involved learner analysis of games, the ability to change level design via graphical editor and co-design of proposed conceptual changes to existing games. Unlike 3M it did not involved the learners then adding new patterns to games using code.

One similarity is the number of patterns presented to learners. In this iteration of the study 3M presented 20 patterns in the menu of options and the Stringforce study selected 14. Their selection criteria for patterns to include in co-design stages included the following concerns; concrete patterns were favoured over more abstract ones to aid the learner comprehension, patterns chosen matched the learners’ capabilities, patterns that were game mechanics were also prioritised as were pattern suggested by the learners.

Synthesis of chapter / discussion

Defining and conceptualising informal education

on Informal Education Pedagogies

To assess the wider use of professional frameworks of concepts, it is potential valuable to test them in the context of wider theories of community and informal learning.

Informal education has the potential to offer less barriers to authorial agency which are engendered by factors such as curricular constraints, practical classroom factors and school behaviour norms.

Defining Informal Education Definitions of informal education are complex and beyond the remit of this literature review. Informal here is not just about a school or non-school environment [@erstad_identity_2012].

Gerber define formal learning as that which happens in school and informal learning as that outside of school [@gerber_development_2001], Sefton-Green [@sefton-green_literature_2004] complicates this view, noting that2 informal learning can take place in formal settings and vice-versa.

Others writers [@eshach_bridging_2007, p. 173; @werquin_recognition_2009] describe learning happens outside of formal institution and where there is little instruction but the learner experience is carefully planned using the term ‘non-formal’ in contrast to both formal and unstructured/informal learning.

Informal, participatory, digital and gaming communities

Digital learning in IILP (GLAM settings) is fertile [@degner_digital_2022; @schwan_understanding_2014]

The focus on historical and cultural artefacts and practices brought by Rogoff, and in particular the concept of guided participation was originated in non-school settings and younger age ranges.

However, the concept has been used to analyse participation in non-formal and formal settings. The following studies are relevant:

- guided participation framed in media literacy @aarsand_appropriation_2016.

Using professional frameworks to help novice game makers

This section examines the use of potential use of these professional tools or processes in an educational context.

Using concepts of design patterns and game design patterns

Werner and Denner built an ambitious assessment elements into a two year programme using Alice to make games. They built a software tool to quantify the levels of computational thinking, using a structure of thinking algorithmically [@werner_fairy_2012]. The results - a limited use of standard CT concepts by students - led them to also investigate the use of students of game mechanics as well as more traditional CS constructions [@werner_children_2012]. They began to identify use of design patterns and then combination of those patterns into large game mechanics.

Using pattern collections and code examples to help students.

THERE IS DUPLICATION AT END - IN TENSIONS

To help revolve the play paradox - of learner choice vs subject exploration [@hoyles_pedagogy_1992] Franklin and friends suggest the use of the UMC framework [@franklin_analysis_2020].

Other work from UMC proponent Lytle suggests a list of extensions to choose from swapping create for choose [@lytle_use_2019-1]. Based partly on the cause of teacher stress caused by the open ended nature of the “Create” part of the model.

Other researchers used to scaffold creation of coding projects by novices [@wang_novices_2021] and note barriers students encoutered including, mapping barriers, other

GSM created a supporting pack for teachers which used challenges themed around categorisation of game design patterns.

The normal practice is geared towards prompts within the software with specific missions.

There is little research published on how the cards were used in practice. Limitations include …

GAP in the resaseach:

No research for GDP pattern collection for to text code games with for CS or game studies in young people.

Link paragraph to game making pedagogies

The problem statement of the thesis

- An overall problem based on Lit review here.

- Discussion of implications of synthesis of the Literature review

- Description on how the RQs frame the problem to help an investigation via the data gathered.

Inequality of access to participatory culture communities (Barrier)

In these more naturalistic settings, Ito and colleagues note that generative activities are the exception rather than norm even in expressly creative communities [-@ito_hanging_2010]. Productive partnerships in communities like Scratch are extremely rare compared to false starts. Studies of the New Grounds site which has a similar aim of creating media collaborations, via collabs, showed a 80 percent failure rate of collaborative projects [@luther_why_2010].

On the other end of the spectrum is the desire to bring open-ended practices into the school setting. We see that a similar pattern in different communities – ABOVE IN MAKING - SCRATCH IN SCHOOLS While the focus of my study will be on family learning, due to the need for strategies to bring game making into schools settings, which I will address this issue. Kafai’s study detailing an emergent peer pedagogy, accepts some of the limits of the school setting but identifies peer practices that show great promise.

Building learner identities to address Inequalities

One significant element of in this process is learner perception of their own limits. EXPLORE RESEARCH HERE.

Barrier - lack of knowledge of cultural processes

Roles and practices to support learners

The tension between autonomous participation in a naturalistic on structured facilitated support is one that is also explored in the extensive literature exploring project based approaches. Here advocates of this approach promote the value of open-ended, authentic projects while critics highlight that without support that collaboration is difficult between learners and thus needs to be scaffolded with structured activities and taught input [@kirschner_why_2006; @kollar_collaboration_2006]

I mention this as the literature surrounding the mature field of Project Based Learning may be a good source of inspiration for tactics to address issues of scaling

Roque makes a convincing case for the unpicking of the supportive and collaborative roles of parents and facilitators to build this capacity and awareness of family learning roles. However, while the design of the FCL programme was effective to build parental confidence and increase overall accessibility, it left questions about the effectiveness of the process to enable learning at home.

We can compare the difficulties of scaling of this hybrid setting (FCL) with more structured, and more naturalistic learning environments. It can be tempting to see the process of hanging out line in the frame of Ito’s online and social participation in informal communities as infinitely replicable. Such online communities are out there. It is up to learner to navigate and extract learning and skills as they see fit.

Tensions surrounding authenticity of tool use- move to LIT REVIEW / END DISCUSSION?

Rainer, Bolton and other practitioner-researchers agree on the potential and value of exploring other subject matter - e.g. literacy, maths, science and history - and undertaking authentic project work within a drama frame [-@rainer_drama_2012].

This authenticity has several relevant dimensions in this study including: audience; toolset; and supportive processes / documentation. This section explores the these dimensions of authenticity and the resulting relationships with agency of the learners.

PBL is adapted to schools in many settings thus, authenticity is “on a scale” in PBL The concept of an authentic-as-possible project is a key tool for educators to support game making via project based learning [find support]. One advatange of working with digital tools is that if issues of complexity and cost can be addressed access to laptops and the internet allow learners to use very similar production tools to professionals.

Key message: authentic tools and processes can increase agency but facilitators should use them with careful curation - as there are negative effects too

<!– An unusual approach so why?

- involvement with mozilla / teach the web

- authenticity - link between developer community and education, global in scope

- can use a cut and paste, remix, irreverant approach - link to media activist / hacktivist pirate cultures. other unexpected Benefits

- could bring in other web creation resource, piskel, –>

Research on project based learning using technology supports the motivational and inspirational factors of authentic tools in the fields of STEM computing [@garneli_computing_2015-1; @humble_use_nodate], media making and STEM in general. [IF SO FIND THIS ]

Theoretical Framework

Socio cultural approaches and the primacy of context

This focus on the environment and context is in line with social and cultural lines of research. Socio-cultural research and perspectives can be broadly described as…[@barnett_ecosystem_2019]

A central assumption underlying

this essay is that any abstraction of ‘content’ from its ecological functioning (e.g., use within a particular situation) is likely to undermine its perceived value for any situation (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Nathan, 2012) or

the learners’ belief that they are likely to do something meaningful with that which they are learning.

This primacy of context described above underlies much of the social turn of educational and psychological research.

As my study seeks to address cultural factors which act as barriers to participation in digital making, it requires a method of research which allows the detailed description and evaluation of complex, emergent learning environments.

There are a range of valid methodological approaches suited to this study. These include participatory design Muller, 2007), ethnography and guided participation, communities of practice , Activity Theory .

I have chosen to use activity theory as a base for the the theoretical framework of this study and to supplement it with the technique of design-based research. I also draw on the work of Rogoff and the use of three planes of activity to analyse complex community actions.

Primary framework Activity Theory

In the literature review we explored sociocultural views on learning and development on learning in created cultures.

The focus of this study is on the construction of shared meaning and practices as part of an emerging community of game makers.

To do this I adopt a sociocultural approach and specifically cultural historical activity theory CHAT in the form of design-based research.

Design-based research and formative intervention studies within educational field

My own research in game making is an experimental approach to create a new learning design. I have worked with young learners, local families and undergraduate student helpers to evolve a game making design. A key driver of my research was to explore the potential to draw on family experience in learning activities by working with families to make games together.

MOVE UP - MERGE I propose that this environment is a fertile research base to jointly create learning activities with a wider potential application. To facilitate this goal I have taken a design-based approach which acknowledges the importance of context in educational research [@brown_design_1992].

Design based research is a varied discipline which can take a multitude of forms [@mckenney_educational_2021]. The core elements include: research as an intervention, iteration, involvement of participants in the evolution of designs, and a flexibility of research outcome based on how events unfold [@easterday_design-based_2014].

Penuel [-@penuel_emerging_2014] describes design based researchers as an eclectic in approach but that there are calls for more formalisation.

One of the key motivations of this approach is to produce educational research that has a high utility for practitioners through developing theory that is rooted in contextual practice and which can produce new pedagogies and resources [@cobb_design_2003].

Justification of choice (esp compared to contructionism)

MOVED FROM ANOTHER SECTION SEE IF IT FITS.

Before progressing to explore the details of the design, I want to briefly explore how this process brought into focus some of they key debates and issues of design based research.

- mutual appropriation and ethics of participation rather than extraction

- generating material suitable for sharing as research but also basis for starting other communities, be this via tools process or other

- the difficulties of transmitting research outcomes to non-academics - give positive examples.

AGAIN MOVED Active stance of research: There is an increasing stream of research work which places the researcher as an agent of change in a complex world where the need for systemic change is apparent and urgent.

Context and Generalisation of results:

Barab and Squire [@barab_design-based_2004] describe the messiness of design-based research and that this creates a challenge to the researcher of how to present results in a coherent way which is of use to other practitioners. There is a tension between sticking closely to the context of the research and the concrete specifics or stepping back to generalise and being lost in abstraction.

This context of this research, which is x,

Why not constructionism

Much of the foundational literature on game making focuses on personal dimensions of learning (Harel and Papert, 1991; Kafai and Burke, 2015; Kafai and Resnick, 1996). They draw on Papert’s constructionist approach which extends a piagetian take to propose that construction of personal knowledge happens best where learners can experiment and manipulate [@ackermann_piagets_2001] . Such a focus on individual learning is problematic from perspective of sociocultural approaches due to a tendency to ignore both contextual factors influencing the learning setting and the evolving use of resources, processes and shared understandings by emergent communities of learners oloughlin_rethinking_1992

While noting the focus “individualist” approach of many studies from constructionist researchers, [@barab_practice_2000].

The alignments noted by Barab between constructionist approach and apprenticeship also apply to DBR namely “learning occurs within a context of use, learning is frequently collaborative, learning as authentic, learning as inquiry-based not transmission-based” [@hay_constructivism_2001] p. 3. Thus the broad claims are in alignment with wider socio cultural approaches.

Constructionism as a movement has done important work in creating design guidelines but much weaker as either an underlying theoretical or analytical framework.

NOTE - THERE IS IMPORTANT WORK HERE ON AUTENTICITY- and the potential tensions with agency - ie if authenticity is working a the elbows of professionals, students have less ownership over the process. [@hay_constructivism_2001, p. 34]

WHAT DOES BROADER FRAMEWORK OFFER?

Cobb [-@cobb_where_1994] identifies two broad schools of constructivism, one focusing more on individual cognitive processes which follows the work of Piaget and the other drawing on the academic lineage of Vygotsky which locates knowledge formation as a cultural activity.

Barab and Squire [@barab_design-based_2004]

For the focus of this study on developing game coding abilities particular aspects of importance are of understanding of the importance of context, and the ongoing development of cultural artefacts. NOTE - Thus in the next chapter particular attention is paid to the development of the artefacts and processes developed as part of the learning design.

As we have seen in the literature review on game making, context is explored in the three main streams of research into tools and processes to support game coding namely: schools environments, professional contexts; and informal spaces.

Conceptualising informal education via foundational theory

Foundation sociocultural approach which goes beyond a conception of transmission model of learning and embraces learning in context.

-

Vygotsky (and friends) - foundational ideas - activity as unit of analysis - mediation via objects and ideas [@luriia1976cognitive]

-

Wertsch and Cole - community and context as vital in studies, role of cultural mediation in development, role of objects to study human culture [@cole_beyond_1996-1; @cole_culture_1995].

-

Rogoff - community of learners and 3 foci as a way to frame this in education

The vital role of cultural mediation in development [@cole_beyond_1996-1]

This clearly aligns with community-based digital making and the use of objects as mediated objects and creative processes which facilitate and constituent participation.

Currently Parked from Literature REVIEW

Mantle of the Expert as a processes drama

A way of leveraging some of the processes outline above in a schooling context.

The salient features of MoE. Broadly speaking, Mantle of the Expert draws on three teaching modalities: inquiry learning; drama for learning (closely related to dramain-education, or, as it is sometimes called, process drama); and what we might call “expert framing” [@aitken_dorothy_2013].

Heathcote discusses authenticity in detail in her writings [@heathcote_dorothy_1984]. The focus on authenticity, to align needs interest and object interests - see notes - and the creative work of the facilitator to align them In an illustrative case study on computing the needs interests are to respond to the percieved authentic need of a scenario, and the object interest was the subject matter of learning to the computer system to carry out a task.

Writing in role or writing in action is a technique used in MoE [@hinton_workplace-focused_nodate]

Rainer and Bolton explore some of the rigidity of the MoE approach in terms of time allocated and other factors. Rainer outlines a wider scope of a process drama [-@rainer_drama_2012].

Other forms of process dramas and STEM education

MoE is one form of other process drama. Others exist. They share similar aims. MoE can be seen as formulaic [@rainer_drama_2012], or prohibitively time consuming [@heathcote_drama_1994].

Rainer chapter [@rainer_drama_2012] also highlights authenticity in different phases, both in activity and in assessment to aid metacognition.

Existing research shows value in STEM education to address barriers associated with identity issues [@fields_picking_2013; @gill_process_2012].

My own work with Manchester Met University drama education department explored the value of coding in role. [@caldwell_drama_2019]