Mick Chesterman

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8005-2390

Abstract

The creative processes involved in undertaking computing projects in an educational setting have a significant potential to deliver transformative learning experiences. Pedagogies and frameworks to support design approaches in education are valuable to teachers to guide and maximise the experience of their learners. This chapter describes and explores some of the strategies that can be used to support the delivery of design and project based approaches. It covers the value of creative communities in the design process, key teaching techniques aligned with design-based approaches, the benefits and processes of project-based learning (PBL), and tactics for overcoming limitations in delivering PBL in the classroom.

Introduction

The creative processes involved in undertaking computing projects in an educational setting have a significant potential to deliver transformative learning experiences. Pedagogies and frameworks to support design approaches in education are valuable to teachers to guide and maximise the experience of their learners. This chapter describes and explores some of the strategies that can be used to support the delivery of design and project based approaches. To start, I focus on the value of creative communities in the design process. I then outline three teaching techniques aligned with design-based approaches to computing projects. The second half of the chapter takes a broad look at some of the benefits and processes of project-based learning (PBL) and ends with some tactics for overcoming limitations in delivering PBL in the classroom.

The Power of Communities

A project based approach to learning coding and computing can be be supported by the home environment. For example, enthusiastic older family members may take young people to Maker Fairs or engage in other community coding activities. Family members may buy creative computing kits or access resources such as YouTube videos or online forums for specialist interests like robotics, games or other forms of digital making. However, access to this kind of computer enthusiast community is not available to all young people. The following initiatives aim to address this by providing entry points to community-orientated coding activities.

Code Clubs are out-of-hours school clubs run by teachers or volunteers. Running a code club is a good way to build a lunch-time or after school community of coding enthusiasts. Code club was originally an independent organisation which is now part of Raspberry Pi Foundation. A large number of high quality, colourful and attractive resources are supplied free of charge on their website.[^1] The resources provided can be printed out and serve as step-by-step tutorials. Resources also contain challenges that encourage further experimentation by learners.

Coder Dojos are monthly events run by volunteers at weekends. They often focus on creative, engaging computing. I have volunteered at some events and been impressed at the dedication and inventiveness of the other volunteers. There is an inspiring diversity of activity at events. At a typical Coder Dojo some learners will use existing resources to support multi-media coding in Scratch, others will try out new and experimental work, perhaps hacking Minecraft, creating games with code engines or trying new physical computing projects. Often volunteers bring their own children who act as guinea pigs testing activities out on their family before bringing it to a Coder Dojo. To find out more visit the Coder Dojo website.[^2]

The Coolest Project is another project of the Raspberry Pi Foundation. It takes the form of an online competition and real-world showcase that individuals or teams apply to take part in. The Coolest Project helps generate a framework and motivation for projects. This experience allows students to tackle problems in a radically different way to much classroom teaching. Projects provide opportunities to engage in authentic coding practices including designing for real users, collaboration with other students, project planning, debugging faulty code and repeated revisions to fine tune the desired result.[^3]

Coder Dojos are family-focused events taking place outside of school and are therefore less easy for teachers to engage with. They are, however, a good source of inspiration for teachers looking for creative project ideas for their classroom. In contrast, both Code Clubs and the Coolest Project are suitable to run inside schools by computing teachers. Running lunchtime or after-school projects, while not reaching all pupils, can be a great way to showcase the engaging and creative nature of hobbyist computing projects.

Communities in Educational Theory

The power of communities has been highlighted by academics as part of what is known as the social turn in educational. This is a turn away from more individualised ways of learning which focus on efficient transfer of knowledge from teacher to the pupil. Instead the focus is on how learning happens through participation in communities and culture, in other words a socio-cultural approach. Community in this educational context can motivate and provide support for participation in a creative process. Barbara Rogoff [-@rogoff_developing_1994], a researcher of socio-cultural approaches to education, has described an educational process she calls Communities of Learners. Rogoff sees this approach as radically different from both instruction based models of learning and pure discovery learning (where learners are left to their own devices). In this model participants have different levels of expertise and varied roles in a learning system working towards an authentic goal. Rogoff notes that observing this kind of learning can be confusing to teachers and parents used to more instruction-based approaches. Such a learning community in full swing can seem chaotic. However, complex and productive learning is happening in ways that we, as teachers, may be unused to. This chapter helps unpick some of these practices and explore ways that educators have structured their learning environments to take advantage of this powerful approach.

BEGIN BOX

Are you making the most of the power of communities in your classroom? Before you start your next unit of work ask yourself some of the following questions.

- Are there regular opportunities for learners to work together during your unit of work? How often will students give and receive peer feedback?

- Are there examples of similar work from other students available for your students to examine and perhaps build upon?

- Can you draw on the roles or identities that students have adopted in their previous school or home activities? Are learners able to reflect on the specifics of those roles to contribute to the effectiveness of their engagement in teamwork?

- Can you help your learners make connections between their computing activities and other professional or enthusiast communities outside of the classroom?

END BOX

Design-based Approaches in Computing Education

Designing as a discipline involves a community of both producers and users. Design-based approaches have been adopted widely in software production, creative industries and wider business contexts. These design principles and practices are also relevant to education. For example, we may be used to seeing students motivated by producing something for a real audience. Design projects allow students to develop important 21st century skills like problem solving and communication, and creatively responding to real life contexts. In the following sections I will explore the design-based approaches of iteration, design patterns and the Use-Modify-Create model.

Teaching Technique - Iterative Design

Iterative design involves repeatedly coming back to reflect on the initial outcomes of creative goals and revising them based on results. The process involves: goal setting, creating quick prototypes, user testing and evaluation, revision and ongoing reflection. The process is iterative in that testing and revision of the prototype design can be repeated until the desired result is achieved. Iteration is also a key part of a more general scientific method of testing a hypothesis and revision based on your analysis of results. The idea of a repeated (iterative) spiral approach which both deepens understanding and improves the end results is popular both in education and industry. In software and design industries it is often referred to as Design Thinking and Agile approaches. In education this approach is referred to in concepts like the spiral curriculum and the promotion of student mastery.

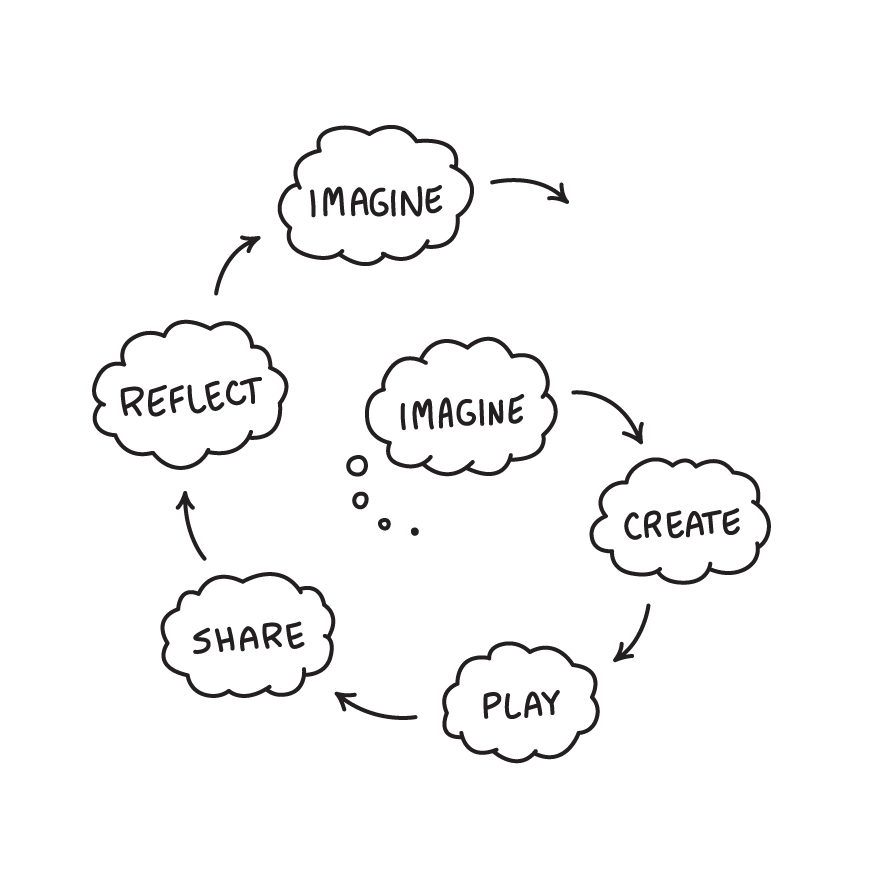

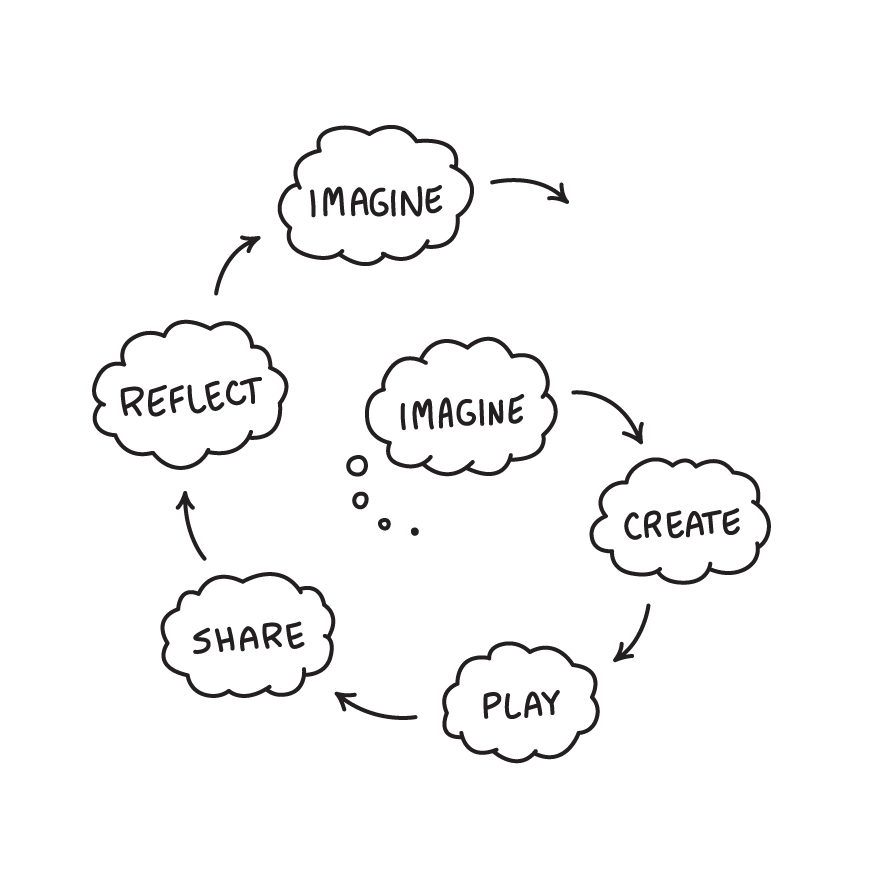

Michel Resnick, a researcher involved in the Scratch project at MIT illustrates an approach to design-based education through a creative cycle. The five circular stages are; Imagine, Create, Play, Share, Reflect and returning to Imagine once more. The model encourages both parents and teachers to create a supportive environment for creativity.

Figure 8.1. Diagram of five circular stages; Imagine - Create - Play - Share - Reflect - Imagine

Resnick [-@resnick_scratched_2012] describes the foundations of the design-based approaches in education as; engaging in design activities, exploring personally meaningful topics, collaborating with others, and deepening understanding through reflection. The key reason to adopt these principles is to increase engagement via sustained participation in computing projects for a broad range of learners.[^4] One of the sources for sustained engagement is when, as part of the iterative process, learners are able to test and then revise their creation or experiment based on their own evaluation. Another factor is the importance of a community in the design process, as a real audience for creations, as a source of inspiration and as peer evaluators in the testing process. The above principles embody key elements of inclusive practices contained in Universal Design for Learning (UDL) including: allowing students to demonstrate their knowledge in a multitude of ways and of allowing students to follow their own interests and motivations [@capp_effectiveness_2017].

### Teaching Technique - Worked Examples and Design Patterns

Design patterns are most commonly used for computing students at higher education to teach object oriented computing but they are also useful for all levels of learners. Design patterns are rooted in real-life incidences of problems that are often solved in a particular way. They are concrete examples of coding principles in context. Design patterns can help the development of coding communities if more experiences coders take the time to document the patterns they use in an accessible way for novice coders. In computing education there are similarities between design patterns and a technique called _worked examples_. The National Center for Computing Education (NCCE) have promoted worked examples as a classroom activity by creating a Quick Read document for teachers on the subject [^5]. Both worked examples and design patterns act as a way to demonstrate underlying principles in practice. For both approaches showing working code used in a particular context helps students to analyse what makes it work and why it is a suitable solution.

For educators the use of design patterns and worked examples can help support learners develop coding proficiency by providing scaffolding and modelling good design decisions. However, one of the challenges for teachers of using worked examples and design patterns is how to integrate them into student-led design challenges. You may be able to create a menu of printed or online patterns or examples that students can draw on as needed. Perhaps particularly common examples can be modelled to the whole class when it is clear that many students will benefit from that approach.

### Teaching Technique - The Use-Modify-Create model

The teaching technique Use-Modify-Create (UMC) has the potential to both to limit learner anxiety for novice coders and to scaffold the acquisition of coding and computational thinking concepts [@lee_computational_2011]. A breakdown of each stage follows.

**Use:** In the _Use_ stage, coders build a familiarity with coding interfaces, code structures and syntax through scaffolded approaches which involve interacting with the program code and what it produces.

**Modify:** In the _Modify_ stage learners progress to working on real projects created by others. Learners deepen their knowledge of coding structures and practices by altering existing projects and templates to suit their own aims.

**Create:** After novice coders become more familiar with patterns of code design in use in the modify stage, they can progress to replicate such patterns in other code that they create from scratch.

A study involving five hundred 9 to 14 year-olds found that the UMC approach can balance a structured approach with more student-led exploration [@franklin_analysis_2020]. The researchers also found that the students enjoyed the UMC approach as they had more choice and agency in the process. This is supported by other research which compared UMC with a starting-from-scratch approach and found higher student engagement for those in the UMC group [@lytle_use_2019]. The researchers found that because students using UMC had more time to play around with code, they were able to add their own personal touches and that this ownership over the code sustained their continued engagement.

Researchers Kafai and Burke [-@kafai_social_2013] argue that a shift from writing programs from scratch to modifying and remixing them is inline with socio-cultural teaching approaches. They coin the term computational participation to reflect this change of focus. They also note that such remixing is helped by online coding communities, especially those aimed at novice coders like the Scratch community (described below). They encourage educators to avoid focusing solely on technical possibilities of coding environments to embrace the potential of online coding communities despite associated challenges. One challenge of teachers embracing remixing practices is to distinguish the legitimate remixing of work from less productive kinds of copying. In addition participation in online communities requires learners to concurrently build both technical and participatory skills which may also be challenging. The following case study examines ways in which the online Scratch community is facilitating design-based learning. It makes a strong case for the value of these approaches and asks how some of these benefits can be made more inclusive for learners who would struggle to take part in such a community independently.

### Case Study - How the Online Scratch Community supports Design-based Learning

Scratch is educational software which uses a block based coding approach and a set of tools to develop audio and graphical assets to help the creation of multimedia coding projects [^6]. Scratch as a project excels in its user community. There are over 75 million users of the site who have created 80 million projects. Activity increased during COVID restrictions in 2020 and 2021 with over 20 million user comments in the month of March 2021 alone. The online community allows young creators to connect with others to share and get feedback on their work. Such community interaction sustains repeated effort to build student mastery in the form of fluency in the design and coding process. Here are some of the key features of the online Scratch community with tips to integrate these into your computing teaching.

**High diversity of creations:** The process of keeping such a large community up and running and safe for young people requires a lot of resources. However, the effort is justified as it has become an extremely rich source of inspiration for young creators. A simple search of the site for projects like games, creative greeting cards, storytelling projects and pretty much any digital product you can imagine will yield a multitude of results. As teachers we can draw on this resource to demonstrate diverse creations and encourage our learners to adapt existing work based on their own interests.

**Diverse ways to participate:** Learners can engage with the online community in a great variety of ways. If they use it outside of class, learners may just play or comment on the games of others. They may use it to create their own projects but not engage in the more social elements of the creative process. They may like a smaller section of the community become extremely active in creating and collaborating with others on shared projects.

**Encouraging project iteration:** Scratch encourages the remixing of others' projects and makes it easy to create different versions of your own projects. This encourages sharing drafts for feedback via peer comments. This public sharing and feedback has been shown to encourage the development of new features in users' creations. In the classroom, teachers may need to balance the more disruptive possibilities that the ability to publish inappropriate material online with the potential to build student autonomy and reflection.

**Supportive and authentic audience of fellow creators:** Due to the high numbers involved in the online Scratch community there is a good chance of finding peers who are also interested in specific subject matter. Peer collaboration between community users is motivated by these shared interests. The potential and depth of collaboration of this community can be impressive. Roque and colleagues [-@cress_supporting_2016] have described this in detail.[^7] The researchers describe how individuals find each other and group together by forming _studios_ and then recruiting other members to work on joint projects. This is sophisticated behaviour which mimics real production processes. It is carried out by young people with a high degree of independence. However, the researchers concede that such collaborative production is only carried out by a very small proportion of the online creators. Teachers should be aware of a key challenge identified by the researchers, namely how to replicate the benefits of collaborative community activity for young people who have less experience or confidence. In response Roque [-@roque_family_2016] went on to develop related programs including online project exhibitions, competitions and off-line family-based projects to engage under-represented groups. As educators, we can take inspiration from this process of replicating the highly engaged, organic feedback and support of the chaotic online community into a more offline and structured design-based environment. The second half of this chapter addresses ways you may be able to rise to this challenge using project-based approaches.

BEGIN BOX

### Activity - Using Design-based Approaches in the Classroom

You can ask you self the following questions to try to help you use some of the beneficial aspects of design-based approaches in your classroom.

- Are learners able to explore exemplar materials to inspire and shape their creative ideas?

- As they plan, are learners able to think about and articulate the perspective of the real or imagined users of the designed projects?

- Are learners helped to come up with ideas through ideation techniques that scaffold the creative process?

**Follow-up Resources:** I have created several online courses which explore hands on ways to use design thinking in education and community work as part of Manchester Met's Rise initiative.[^8]

END BOX

## Projects and Project Based Learning (PBL)

Project-based learning is a wide set of approaches that seeks to facilitate learning though undertaking practical projects. Students often complete projects in groups. Students develop target knowledge and skills in the context of a real or simulated problem that they must solve. Using projects is one of the 12 teaching principles advocated by NCCE.[^9] In the next section I cover the characteristics and potential of project-based learning (PBL).

Researchers Blumenfeld and colleagues [-@blumenfeld_motivating_1991] argue that school disengagement is caused by work that bores students. They found that project work incorporating learner choice and involving real outputs is motivating and can sustain student engagement. The pervasiveness of digital products in our lives offers a wide-range of choices of computing project outputs including: websites, games, wearable technology, phone apps, robotics and other physical computing projects. Thus, computing education is an excellent vehicle for a project-based approach to learning. However, Blumenfeld's research cautions that implementing PBL in classrooms is not straightforward. I cover barriers to PBL and ways to overcome them in the final part of this chapter.

Academics have worked with expert practitioners to create PBL frameworks to help teachers to plan and deliver projects, and to recognise the complexity of some of the learning that takes place. The following outline of PBL elements is a synthesis of several of these frameworks with additional commentary on how this may apply to computing projects.

**Challenge:** The focus of the project should be a relatable problem or question that is does not have one straightforward solution. Software and electronics projects can fit this brief are thus very suitable candidates.

**Authenticity:** Real-life relevance of projects helps engage student as they make connections to their interests and communities. As mentioned in the section above, many forms of coding projects from phone apps, websites and games are real and relatable goals.

**Sustained and Collaborative Work:** Adequate time must be allocated for sustained project work. Students should work together and be given the chance to revise projects. This is perhaps one of the greatest challenges to delivering computing projects in a school setting.

**Public Project:** The creation of a shareable, public object helps learners focus and to design for others. It can also act as a focus for discussion within the classroom. Sharing of computing projects within the classroom could be supplemented by presentation to a wider audience.

**Student Voice and Choice** Giving students choice over the focus of their project increases their engagement. Participation in discussions about project direction builds student autonomy. The high level of saturation of digital products into the experience of many young people's day-to-day lives can help shape students' interests.

**Reflection and Critique** Self-reflection may be informal at times but also guided by class processes like learning journals. It can also involve peer feedback or input beyond the classroom to bring authentic perspectives. Reflection could also happen in a digital form via an online journal or templated digital documents.

### Teaching Technique: Supporting PBL in Computing Classrooms

PBL and other design approaches are aligned with UDL in many ways. For example, they all benefit from a collaborative community and a real or imagined audience for public products as a way to increase learner motivation. They also advocate structures for students to chart their progress and support feedback. One of the central tenets of these approaches, the importance of learner choice in projects created, is also one of the most challenging for teachers to enact. One critique of project-based learning, especially where it involves student experimentation and student discovery, is that it can is be chaotic and that it is therefore challenging to communicate high-level concepts. PBL also requires skills, support and planning that are very different from traditional teaching and therefore may be difficult for teaching staff to implement. For example, practitioners must build their ability to switch between facilitating students operating freely to then guiding them in the process of revision and critique. Having resources and clear stages to your project plan to help this process is vital. This section outlines the typical stages of PBL and how to adapt them to a computing context.

**Start with a driving question or mission:** The project goal for computing projects is often to create a digital product in response to a need or design brief for a specific audience. Add in detail and link to real world problems at this stage to maximise learner engagement. Decide the limits for students projects and outline these clearly from the start to avoid having to dampen down their enthusiasm. For example, if creating a 2D game instead of a 3D one is better suited to the technical ability of students then be clear about that limit from the start of the project.

**Designing a plan and resources for the project:** Decide what part of the curriculum the project work will develop. Use your knowledge of the curriculum to put resources in place to support the learners as they undertake the project. Not everything needs to be explicitly taught if you can signpost your learners to those resources. Having an online or paper-based resource bank for students to access and navigate can be extremely useful.

**Monitor pupil progress:** As the project unfolds, keep students on track by having a realistic schedule for project stages. Check that you are consistently signposting students to the relevant resources for the project choices they have made and for the stage that they are currently undertaking.

**Assess emerging project processes and outcomes:** Ongoing feedback and assessment is vital. Build in opportunities for reflection, peer feedback and revision. Can students share prototypes of their digital products? Can you support then to recognise if they are working effectively as a team? How can you support them to make connections to the underlying curriculum knowledge?

**Evaluation:** You may evaluate the end piece of work created by students, the way they have worked together and the skills used to undertake different stages of the project. You can validate what the students have learned and identify areas for future development.

If you would like detailed information and case studies on PBL there are online resources provided by numerous organisations including Edutopia[^10], PBLworks[^11] and the UK-based Edge Foundation.[^12]

## Creatively Overcoming Limitations to PBL

This section looks barriers to PBL and tips and strategies that have been used by other educators and researchers to overcome these barriers in the context of computing.

**Sustaining the effort - Time challenges:** In research on barriers to undertaking projects in schools, teacher commonly cite time restrictions due to curriculum pressures. Resnick and Rusk [-@resnick_coding_2020] suggest that if possible, double lessons are helpful for hands-on coding work and to allow the design process time to unfold. They also advocate that at times a whole term should be devoted to undertaking a project. This sustained effort allows pupils to return to tweak and improve trickier coding and design challenges, thus supporting an iterative approach. In addition, cross-curricular projects may free up more time by linking with other subjects which are allocated more time, especially in KS3. For example, you could link a computing project with mathematics by asking students to create a game that teaches mathematical concepts. This could both deepen students' learning of particular mathematical concepts and allow for the kind of repeated hands-on practice that builds coding fluency.

**Advocating the Value of PBL for Inclusion:** As with design-based approaches, PBL aligns well with UDL, specifically in the way students can bring their own interests into their creation of a public project. Both frameworks encourage teachers guide and support project work with scaffolded support and ongoing feedback. As educators, we can highlight importance of creating inclusive classroom environments to our line managers to advocate for the time, training and resources needed to undertake project-based learning.

**Artefact-based Assessment:** The tension between rote-learning approaches that may be used to prepare students to reproduce knowledge in written exam questions and the need for more fluid programming experiences raises an important question. How can some of the more flexible techniques for observing and assessing learner progress be brought into classroom practice? As a possible response, the NCCE promote the use of Artefact-Based Questions (ABQs) to assess project work. ABQs are questions based on the digital or physical artefacts that students create as part of their projects. ABQs allow teachers and students to link the problems students have encountered and solved in their computing projects to the requirements of the computing curriculum. Teachers can focus in on specific areas of the students' work and ask about details of the code structure and implementation. ABQs can also address design issues and processes. For example, how the project outcomes compare to the original goals, how feedback was implemented, about group work and overcoming challenges and the design challenges.

**Authenticity of Projects:** As mentioned before, computing is blessed with the potential to create digital and physical projects that are recognised or relevant to young people. However, sometimes the process of finding authentic audiences and processes to motivate learners within a school setting is not simple. The following activity may help bring realness to student projects.

BEGIN BOX

### Activity - Meeting the Challenge OF Authenticity in the Classroom

Here are some tactics you may be able to use to link projects to real issues and activities beyond the classroom.

- Draw on community members to set a local challenge that resonates with your learners.

- Use other members of staff in other subject areas to pose a school-based problem. This could be subject-specific or a pastoral or cross-curricular issue.

- Establish links with industry or social enterprises to set an authentic challenge within a work context.

If you draw on experts, staff or community members they do not need to be there for the full term of the project. You can use visits or video calls at the start and end of the project. Most importantly, be sure to draw on the experience of students and use their ideas to shape possible responses to the challenge in early stages.

END BOX

BEGIN BOX

### Case Study - Game Making as a motivational and authentic computing project

My own studies are in game making. This section gives a short summary of a game making program that I have developed which is an example of an inclusive approaches using projects. The learning model evolved via a design-based approach where I responded to the needs and input of learners, specifically a local primary school Year 6 class and a group of home-educated families. As activities developed, they aligned quite directly with PBL and inclusive practices of challenge, student choice, authenticity and providing support to help participants navigate their learning experience.

I have brought the techniques used together to great an approach is called the 3M game making model. Full details and online and printable resources are freely available.[^13] To start, learners are given a challenge to fix and customise a broken and incomplete platform game. The process of starting with a template - which learners are supported to understand, tweak and then make their own additions to - is in line with the Use-Modify-Create model. I adopted UMC in response to participants being confused and slightly overwhelmed when given a totally free range in their technical and creative choices. Choice for learners is present as in the way participants are given a wider range of different game design patterns and narrative and aesthetic choices that they can add to their game. Learners can draw on their knowledge of playing or watching games to choose familiar patterns which include: jumping on enemies to zap them, add player lives, add new levels or change level design. The process of choosing game design patterns and accessing resources to implement them creates an iterative and scaffolded approach to using a diversity of code structures. Resources that help students chart their own progress are also provided in the form of a concepts map and extra missions and motivational methods. Creating a game to share with their peers and friends in the classroom or online is a simple and tangible way to bring authenticity to the project. Regular play testing helps students to imagine their audience to hone the game to maximise playability, and provoke reflection on project progress. This process helps the learners stay motivated and focused. Physical computing can also be brought into game making projects if participants can build their own arcade machines using authentic arcade buttons and joysticks and simple electronics.

END BOX

## Conclusion

Motivation, participation and peer learning does not happen in a vacuum. In this chapter we have explored the value of creating a learning community of coders working on projects that are both authentic and linked to their own interests. To help this to happen, we can draw on some of the rich research and resources that are available from different streams of practice including project-based learning, UDL and design-based approaches. What many design and project-based approaches have in common is their focus on learner choice, sustained hands-on making and frameworks for facilitation, observation and assessment. For an accessible and convincing summary of project based approaches and their adoption in a classroom setting see the review by Barron and Darling Hammond [-@barron2008teaching].

We have explored the tension between creative processes involving learner choice and teaching to the more prescriptive requirements of the computing curriculum. To help bridge this gap the NCCE have created resources drawing on socio-cultural research to offer guidance on PBL, observation and pair programming. As teachers seeking to close an achievement gap between the higher and lower achieving students, we have a responsibility to integrate such methods and evaluate their potential for our learners. Sharing case studies of inclusive project approaches is one way to do this. I hope that this chapter has encouraged you to keep exploring authentic coding practices in the classroom and to share your experiences with others. To continue this journey there are many forums where teachers share practice; these include CAS forums, blogs, twitter posts and so on. In particular, there is a twitter hashtag of #casinclude which encourages computing teachers to share inclusive practice. To fully explore the potential of projects let's share and encourage others to share how we have used design and PBL approaches in our work.

[^1]: https://coderdojo.com/

[^2]: https://projects.raspberrypi.org/en/codeclub

[^3]: https://online.coolestprojects.org/

[^4]: https://mres.medium.com/ten-tips-for-cultivating-creativity-fe79e7ebb83e

[^5]: https://blog.teachcomputing.org/using-worked-examples-to-support-novice-learners/

[^6]: Scratch is available as a free download at https://scratch.mit.edu/

[^7]: http://tiny.cc/scratch-community

[^8]: https://rise.mmu.ac.uk/category/enterprise/design-thinking/.

[^9]: https://teachcomputing.org/pedagogy

[^10]: https://www.edutopia.org/project-based-learning

[^11]: https://my.pblworks.org/

[^12]: https://www.edge.co.uk/edge-future-learning/project-based-learning/

[^13]: https://network23.org/3m-gamemaking